How one clinic uses the Widex Zen sound therapy tool within a tinnitus management protocol is described. Patient outcomes at this clinic—as well as observations relative to implementing the tool and specific issues related to tinnitus patient management—are also offered.

A fractal-based musical chime (Zen) was introduced by Widex as a sound therapy tool for tinnitus management in 2008.1 Since then, this clinic has used Zen for hearing-impaired patients who also reported tinnitus. While the success rate with the use of this tool is very high (over 90%), it is used in combination with counseling, education, and behavioral change.

In this report, the successes and failures in using Zen for tinnitus patients are shared. Highlights of the protocol adopted at this clinic and cases where a judgment of Zen success/failure is not as straightforward will be provided.

A Sound Therapy Tool Inside a Hearing Aid

The Zen is an optional sound therapy tool for the management of tinnitus on all Mind and Clear series Widex hearing aids. Through the use of fractal technology, Zen generates five patterns of semi-random chime-like tones in addition to a broadband white noise that the wearer can use for tinnitus management.1 The wearer can select from one to five Zen program options (aqua, green, lavender, sand, and coral). In each program, the clinician and the wearer can select a specific chime-tone complex and adjust its pitch, tempo, and loudness.

In addition, each program allows the use of the chime-tones, the white noise, the hearing aid microphone, and any combinations of these three stimulus options. When a tone and/or noise is selected, the clinician can select its level to suit the wearer, with or without amplification.

Unlike a typical tinnitus masker, the Zen tones are intended to be used in a passive manner (as a background sound) to distract the wearer’s attention from his/her tinnitus. Sweetow and Henderson-Sabes2 and Kuk et al3 have reported on the effectiveness of this stimulus as a sound therapy tool for tinnitus treatment.

Tinnitus Management Protocol

At the Hearing and Tinnitus Center, all patients with a complaint of tinnitus undergo a complete audiologic and tinnitus evaluation prior to tinnitus intervention. During the tinnitus portion of the evaluation, we measure the patient’s:

- Tinnitus frequency, sound and spectral quality, and loudness;

- Masking level;

- Loudness sensitivity; and

- Degree of residual inhibition.

A detailed tinnitus history and noise history are also obtained. In addition, tinnitus severity is measured with the Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ),4 along with a rating of the degree of tinnitus awareness and tinnitus disturbance.

The patient’s general health (including medical/drug history and sleep history) is also evaluated. Information from the intake questionnaire is integrated into the clinical treatment plan. Any indications for medical referral also will be made during the first visit. Afterwards, the patient is counseled on the nature of tinnitus, as well as the factors that may affect the patient’s reactions to tinnitus. Because the first author (MH) is trained in Tinnitus Retraining Therapy (TRT) and Neuromonics, and educated in the basics of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), contents from all three approaches are used extensively during the patient encounter.

Sound therapy tools are widely used. However, the authors believe that the optimal sound therapy tool should be tailored to the patient’s functional and financial needs. For example, if the patient’s only complaint is tinnitus in the absence of a hearing loss, or if the patient has only a minimal hearing loss, sound therapy tools—maskers, MP3 players with music, meditation CDs, environmental sounds, etc—are discussed. If the patient has tinnitus and a hearing loss, then hearing aids alone or combination units, such as the Widex Zen, are introduced to the patient.

The patient, in consultation with the first author, makes the decision to try a specific sound therapy tool. This way, the patient feels less pressured and more confident in his/her ability to make the decision and to feel a sense of control. Approximately half of the patients decide to use environmental sounds or MP3 players alone as the sound therapy tool initially. It is interesting to note that about one-quarter of these patients return after 3 to 18 months to begin selection of devices.

Fitting of the Widex Zen

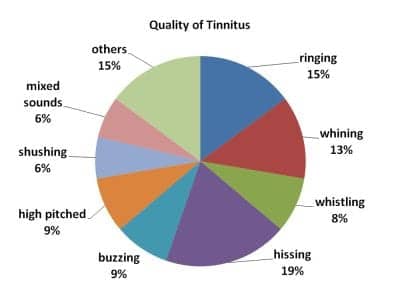

Figure 1. Tinnitus quality reported by patients (n = 48).

At the Hearing and Tinnitus Center, Widex hearing aids with Zen are chosen frequently by tinnitus patients with a hearing loss. In principle, the same hearing aid with Zen can be used in “Zen alone” mode for people with minimal or no hearing loss or for those who do not need amplification from the hearing aid when listening to the Zen program.

The author (MH) uses an “individualized” approach to select the optimal Zen settings for her patients. The tinnitus patients are allowed to listen to all Zen styles/tones in order to select ones that may be the most relaxing for them. They are told that the goal is relaxation with lessened tinnitus awareness. Thus, the Zen tones form the sound background in order to mingle with or diminish the awareness of tinnitus. A significant amount of time is spent to ensure that patients understand the importance of not focusing on their tinnitus and the Zen tones.

In addition, patients are given the noise option in their Zen program. The noise level is adjusted to a level that is slightly below the level that begins to affect the quality of the patient’s tinnitus. Patients also report on their tinnitus loudness when listening through the standard program and the Zen program. For most patients, tinnitus loudness decreases significantly, even after listening to the Zen tones for only a few minutes.

All tinnitus patients are given a minimum of two Zen programs; some patients are given as many as five. Typically, one of the Zen programs has all the options activated (ie, Zen + mic + noise) to be used over several hours daily at times when the tinnitus is most bothersome or prior to bedtime. Patients are instructed to leave the hearing aid in this program and let the Zen tone act as a background. They are asked not to actively listen to the Zen tones.

All patients are also given a second Zen program in which the HA and the noise masker are active (mic + noise). This is intended for daily use by patients with more severe tinnitus, as well as for those with a milder tinnitus who occasionally need a higher level of masking noise to squelch any sudden increase in tinnitus loudness. (Note: Another option recommended by Widex is the use of the “Zen + mic” program for daily use, and a second program “Zen + mic + noise” for use when tinnitus is bothersome.) Both authors give their patients a “Zen alone” program for relaxation and to help encourage sleep.

For most patients, the “Zen Aqua” is selected as the most-preferred Zen tone pattern (it is also the default recommendation). In a few instances, other Zen tones (and noise) are selected to be used alone in a third or fourth Zen program. These tone (or noise alone) programs are mainly used in quiet where listening to external sounds is not critical (ie, relaxation purposes).

All tinnitus patients are followed regularly. The decision on the number of visits is left to the patient. Those who feel they need additional counseling times are encouraged to make more appointments. They are seen at least once during the first month, and at 3 months and at 6 months post-fitting intervals. Patients with more unresolved issues are seen more frequently. The majority of patients only required three visits post-fitting.

One criterion for success is achieving a non-significant score on the TRQ (<17) for two consecutive visits. Patients who achieve this are told that they are successful in reducing their tinnitus to a non-significant level. They are advised to return for annual evaluations unless they feel they need additional help. Again, the patient is being empowered to take control of their well-being.

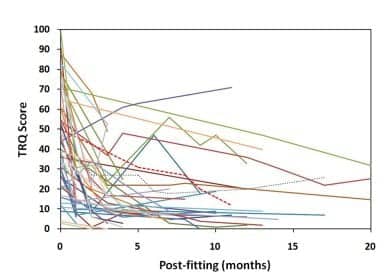

Figure 2. Changes in TRQ scores as a function of postfitting interval.

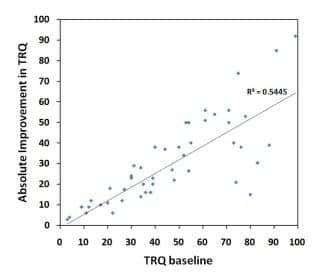

Figure 3. Absolute TRQ improvement as a function of baseline TRQ scores.

Results

Patient population. A total of 48 patients with tinnitus who selected Zen as the sound therapy tool for their treatment were seen between 2009 and 2010. The data reported here were based on intervention duration of greater than 3 months and less than 2 years. Of these patients, 54% were male and 46% were female. Over 75% of the patients were younger than age 65 years. About 45% of the patients had a mild-to-moderate degree of hearing loss, while another 50% had a moderate to moderately severe hearing loss.

While one-third of the patients reported less than 5 years of tinnitus, the majority (65%) had tinnitus for at least 6 years. The location of the tinnitus was mostly bilateral (84%), with about 35% equally loud in both ears. Figure 1 shows the adjectives that the patients used to describe their tinnitus, with most indicating a high-pitch quality. The median baseline tinnitus severity, as measured on a 0 to 10 scale (0 = no tinnitus; 10 = most severe tinnitus), was 6. One-fifth (20%) of the patients rated their tinnitus greater than 8.

The Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire4 was used as the main measure to document the outcome of the intervention. Other measures, including ratings on tinnitus awareness and ratings of tinnitus disturbance, were also performed. However, not all patients reported their awareness and/or disturbance ratings; thus, these two measures are not reported here. In addition, the clinician’s impression of the patient’s success is included as a criterion for discussion.

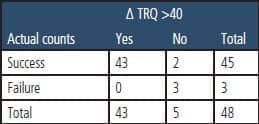

Table 1. Contingency table showing the number of patients who reported greater than 40% improvement on their TRQ scores and those who were rated as successful/failure by the first author (MH).

Changes in tinnitus severity rating over time. Figure 2, plots the individual TRQ scores over time. It shows a general decrease in the rating over time for the majority of patients. Noteworthy is that a reduction in tinnitus rating is seen almost immediately in the majority of patients. This is evidenced in the precipitous drop in tinnitus ratings directly after the initial fitting of Zen and at the 3-month visit. Further reductions in tinnitus ratings are noted after the 3-month visit, although they are more gradual in magnitude.

In some cases, the TRQ scores increased. Fortunately, this occurred only in a very limited number of instances and only with precipitating factors.

Figure 3 plots the absolute improvement in TRQ score from the baseline (ie, TRQ scores at final visit subtracted from TRQ scores at baseline). This is performed in order to determine if the absolute improvement in TRQ scores is related to the absolute TRQ score. Indeed, one can see that the two indices are moderately related with a correlation coefficient of R = 0.74 (R2 = 0.54). This means that patients who reported high negative reaction to their tinnitus also reported the most improvement on their tinnitus from the treatment.

Overall success/failure. In order to compare the relative improvement (Δ) across patients (because of their different baseline ratings), we subtracted the scores obtained at the last visit by the scores measured at the initial visit (baseline) and divided the difference by the baseline score. Or…

Δ = (scores at last visit – baseline score) x 100 / baseline score

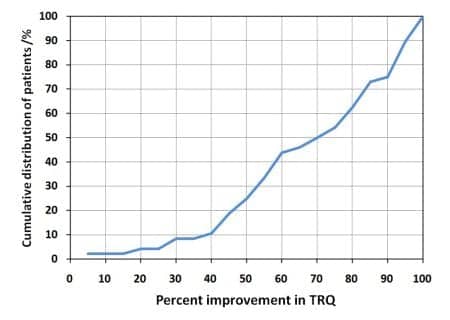

Figure 4 shows the cumulative distribution of patients’ improvement in tinnitus ratings on the TRQ at the last visit. Only 10% of the patients received less than 40% improvement in TRQ scores. In other words, 90% of the patients showed between 40% and 100% relative improvement in their tinnitus as reflected on their TRQ scores.

In order to determine how many patients showed a significant improvement on the TRQ questionnaire, Wilson et al’s recommendation of >40% criterion4 as “significant improvement” was adopted. In addition, this author also judged if the patient’s use of Zen was successful. Table 1 summarizes the number of successful and unsuccessful patients, using TRQ improvement and clinician judgment as criteria.

Of the 48 Zen patients, 43 (or 90%) showed over 40% improvement on the TRQ and were judged by this clinician to be successful. These patients covered a wide range of tinnitus, hearing loss, and demographic characteristics. Thus, the Zen stimulus appears to be efficacious for a wide range of patients with tinnitus.

Mitigating factors. There were two patients (or 4%) who did not achieve more than 40% improvement on their TRQ scores, but were rated as successful by this clinician. In general, patients in this category had a low baseline TRQ score or scored a significant improvement on other measures. For example, one patient had a baseline TRQ score of 22. Despite the reported improvement in how successfully he managed his tinnitus, the “objective” change was not sufficient to result in a 40% improvement in TRQ rating. Another patient’s baseline TRQ score was 87. Although she only showed 37% improvement, her tinnitus disturbance rating improved by 100%. Furthermore, she acknowledged that, with the hearing aids, she functioned well and interacted successfully during all her communication situations.

Figure 4. Cumulative distribution of improvement in tinnitus rating on the TRQ.

There were three (6%) patients who achieved less than 40% improvement on the TRQ and were also judged as unsuccessful by this clinician. One patient had obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and was anxiety ridden. He had a moderately sloping hearing loss and his tinnitus began after taking hydrocodone for back pain in July 2009. The patient was on several medications for depression and anxiety (Lithium, Zyprexa, Lamictal); however, he did not indicate taking any medications for any illnesses on the intake form. According to his wife, he did not take his medications at the prescribed dosage but by “how he felt” at the moment. This could have altered his emotional state and thus restricted his success from tinnitus treatment. As a consequence, his TRQ scores increased from 44 to 71, despite a positive use of the hearing aids. The patient also stated he heard less tinnitus; however, his emotional reaction to tinnitus remained high. Attempts were made to start behavioral therapy with the patient. However, the patient rejected and indicated “…his pills could take care of his issues.”

Another patient with a mild to moderately severe high frequency hearing loss was also diagnosed with an anxiety disorder. He had a baseline TRQ of 80, and a 100% rating on tinnitus awareness and a 100% rating on tinnitus disturbance. After 6 weeks of Zen use, his TRQ fell to 20 and his tinnitus awareness and disturbance improved to 40% and 5%, respectively. At 4 months, his TRQ was 8, his tinnitus awareness was 40%, and his tinnitus disturbance was 0%. Unfortunately, he was in a car accident and he had a concussion. When he left the hospital, his tinnitus became worse. His TRQ score increased to 65; his tinnitus awareness and disturbance both increased to 100%. Given his anxiety disorder, it was hard for him to handle the increase in tinnitus and stay calm. He reverted back to his old habits of excessively monitoring his tinnitus level and seeking “cures” on the Internet. He was counseled on the cyclical nature of tinnitus, the problems of “chasing tinnitus,” and was advised to begin behavioral therapy. Luckily, he scheduled a visit with a behavioral psychologist and is due to return shortly.

The third patient had a mild hearing loss starting at 3 kHz. Initially, he used environmental sounds for his tinnitus, and his TRQ scores dropped from 74 to 22 within 3 months. Unfortunately, he injured his neck during the time he was planning a vacation. This resulted in a high level of stress and anxiety that ultimately reflected in a high TRQ score of 73. With use of the Mind hearing aids, his TRQ scores dropped to 53 (even on a “bad tinnitus day”). He also began behavioral therapy with good progress. He is due back shortly.

Discussion

The Zen program is a very effective sound therapy tool in the management of patients who have tinnitus. Indeed, the success rate encountered by this clinician ranged from 90% (if TRQ score was used alone) to 94% (if clinician judgment was used alone). The average improvement in TRQ scores (as well as tinnitus awareness rating and tinnitus disturbance rating) was around 60% for all three outcome measures.

As a caveat, this high success rate is not guaranteed; success is dependent on a strong patient-clinician rapport and a strong family and support service. Zen is an excellent tool, but more is required in the treatment of tinnitus. The following is a summary of the lessons this clinician has learned so far from these patients.

- The effectiveness of the Zen program is independent of the nature of the patient’s hearing loss or tinnitus characteristics. This effectiveness is seen in the population of patients who covered a broad degree of hearing losses (from near-normal hearing to severe hearing loss) and varied hearing loss configurations. In addition, patients reported a range of tinnitus severity in both ears, centrally or only in one ear. The quality of the tinnitus also varied greatly among patients. That is, it benefits all patients with tinnitus. The exception is the “pulsing” or pulsatile tinnitus. This type of tinnitus is typically less responsive to sound therapy. There were two patients with pulsatile tinnitus in this cohort. Both reported success with the Zen, but both reported no significant change in their awareness of the “pulsing” tinnitus. However, the disturbance caused from the tinnitus was less acute. This may not be fully reflected on the TRQ scores.

- The approach taken by this clinician appears to be effective for the patient population served. Specifically, we recommend letting the patients select the sound therapy tool for themselves. For those who select the Zen program, at least two Zen programs should be used. One Zen program simply has the Zen program (Zen tones or noise) and the master program, and the other program has the Zen stimulus, the master program, as well as the noise stimulus. Inclusion of the noise stimulus is to provide immediate tinnitus relief. While patients are counseled to use the Zen program on a daily basis, they can select Master or Zen or Noise depending on their preference and need for the situation.

- The more severe the tinnitus, the more likely one observes a large change in tinnitus rating (eg, TRQ). The converse (less tinnitus, less improvement) is also true. This does not mean that people with mild disturbances do not benefit from intervention; it simply means that the magnitude of the reported improvement may be less. The fact that over 90% of the patients showed >40% improvement on the TRQ attests to the effectiveness of the treatment. From a clinical management perspective, patients with mild tinnitus are less likely to select devices for tinnitus management. They may be served well with the use of amplification for their hearing loss without Zen, or they may simply use Zen for relaxation. From a time perspective, this may be more efficient for patients.

- The challenging patients are those whose success with the Zen program fluctuates. These patients are more prone toward obsessively monitoring their tinnitus. The personality of these patients typically does not allow them to “ignore” their tinnitus. On a stress-free day, their tinnitus may be manageable and unnoticeable. In the presence of a stressor, their tinnitus returns. It is widely known that stress, even if it may not be the main cause of tinnitus, precipitates and/or perpetuates tinnitus.5 Thus, teaching patients how to manage their stress more effectively is an important component of a tinnitus treatment program. The use of techniques employed in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy6 can help patients better understand their tinnitus, set more appropriate expectations, and help them to modify their behaviors so their tinnitus is less affected by stressful events in their lives. The use of various techniques (eg, meditation, relaxation, and/or biofeedback) can also minimize the impact of stress on patient well-being and minimize the occurrence and impact of tinnitus.

- One thing that should be made clear to the patients at the beginning of any tinnitus intervention is the potential interaction of drugs/medication on the patient’s tinnitus. Despite this clinician’s instruction to all the patients on the potential interaction between drug dosage changes and their tinnitus, such instruction may not be taken to heart by some. While we should all seek ways to improve patient compliance, we should also recognize that, ultimately, the patients’ motivation to change rests on their own shoulders.

References

- Kuk F, Peeters H. Hearing aids as music synthesizer. Hearing Review. 2008;15(10):28-38.

- Sweetow R, Henserson-Sabes J. Effects of acoustical stimuli delivered through hearing aids on tinnitus. J Am Acad Audiol. 2010;21(7):461-473.

- Kuk F, Peeters H, Lau C. The efficacy of fractal music employed in hearing aids for tinnitus management. Hearing Review. 2010;17(9):34-46.

- Wilson P, Henry J, Bowen M. Psychometric properties of a measure of distress associated with tinnitus. J Speech Hear Res. 1991;34(2):197-201.

- Møller AR, Langguth B, DeRidder D, Kleinjung T. Textbook of Tinnitus. New York City: Springer; 2011.

- Sweetow R. Cognitive behavioral modifications. In: Tyler R, ed. Tinnitus Handbook. San Diego: Singular Publishing; 2000.

Citation for this article:

Herzfeld M., Kuk F. A Clinician’s Experience with Using Fractal Music for Tinnitus Management Hearing Review. 2011;18(11): 50-55.