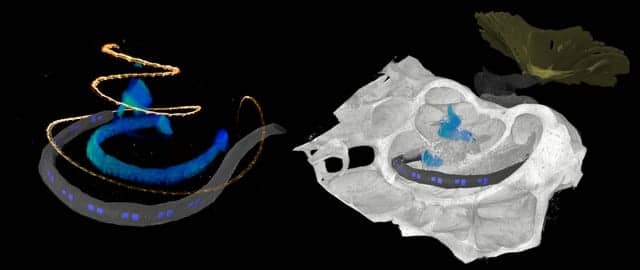

Left: 3D-microscopic image of optical LED-based cochlear implants (blue LEDs in gray silicone encapsulation) with hair cells (orange) and auditory nerve (blue/green) in the cochlea of a common marmoset. Right: Optical cochlear implant in the basal turn of the marmoset cochlea. Auditory nerve cells are shown in the center (blue/green). The tympanic membrane (yellow), malleus (dark gray), and incus (gray) are shown in the background. The stapes is hidden by the cochlea. Image: Daniel Keppeler, UMG.

Cochlear implants enable people with profound hearing impairment to gain a great deal in terms of quality of life. However, background noises are problematic; they significantly compromise the comprehension of speech of people with cochlear implants.

A research team led by Tobias Moser from the Institute for Auditory Neuroscience and InnerEarLab at the University Medical Center Göttingen and from the Auditory Neuroscience and Optogenetics Laboratory at the German Primate Center – Leibniz Institute for Primate Research (DPZ) is therefore working to improve cochlear implants. The scientists want to use genetic engineering methods to make the nerve cells in the ear sensitive to light so that they can then be stimulated with light instead of electricity, as is currently the case. By using light, the scientists expect to be able to stimulate the neurons in the ear more selectively. Now the team has succeeded in taking another important step toward developing the optical cochlear implant. An article detailing the results appears on the German Primate Center’s website.

In collaboration with a team of X-ray physicists led by Tim Salditt, who, like Moser, also conducts research at the Cluster of Excellence Multiscale Bioimaging (MBExC) Göttingen, they were able to use combined imaging techniques of X-ray tomography and fluorescence microscopy to create detailed images of the cochleae of rodents and non-human primates. This determined important parameters for the design and material consistence of optical cochlear implants. In addition, the researchers, who included scientists from the Collaborative Research Center 889, succeeded in simulating the propagation of light in the cochlea of the common marmoset. The results of the simulation show that spatially limited optogenetic stimulation of auditory neurons is possible. Accordingly, optical stimulation would lead to a much more differentiated auditory impression than the electrical stimulation used so far. The results of the study were published in the scientific journal PNAS.

More than 5% of the world’s population, about 430 million people, are affected by hearing loss and deafness, according to current World Health Organization (WHO) estimates. The causes are many: genetic factors, infections, chronic diseases, trauma to the ear or head, loud sounds, and noise, but also side effects of medications. Hearing aids and electric cochlear implants remain the most commonly used devices to rehabilitate hearing loss, the latter being worn by more than 700,000 people worldwide. The electrical cochlea implants allow otherwise profoundly deaf or hard-of-hearing users to understand speech in absence of nonverbal cues, for example on the telephone. However, background noise significantly impairs this understanding. Even linguistic subtleties that speakers convey by changing the pitch or melody of speech cannot be picked up by conventional implants. This is mainly due to poor frequency and intensity resolution. Electrical cochlear implants stimulate nerve cells in the ear by means of an electrical current transmitted from 12 to 24 electrodes. However, the current distributes widely in the fluid of the cochlea, which affects hearing quality. Since light can be focused, the optogenetic stimulation of auditory neurons envisioned by Moser’s team promises to significantly improve frequency and intensity resolution.

The development of optical cochlear implants is a complex undertaking that involves many researchers from different disciplines, from research in basic principles to clinical applications. One factor is the complicated structure of the cochlea, which is poorly accessible for investigation, even by imaging because it is deeply embedded in the temporal bone. However, detailed knowledge of the structure of the cochlea is critical for the development of innovative therapy for deafness.

Researchers rely on animal studies to develop the gene therapy and optical cochlear implants and to test their efficacy and safety. Suitable animal models include rodents such as mice, rats, gerbils, and as research progresses, non-human primates. At DPZ, the Auditory Neuroscience and Optogenetics Laboratory conducts research with common marmosets, whose behavior in vocal communication is similar to that of humans.

“For (late) preclinical studies, detailed knowledge of the anatomy of the cochlea is necessary. We used phase-contrast X-ray tomography and light sheet fluorescence microscopy, as well as a combination of the two, to image the structure of the cochlea of both major rodent models and common marmosets,” said Daniel Keppeler, first author of the study.

“For cross-scale and multimodal imaging, we developed special instruments and methods, both here in our lab and with synchrotron radiation,” said collaborating partner Salditt, professor at the Institute of X-ray Physics at the University of Göttingen, who led the research team in X-ray tomography.

“In this way, we were able to gain detailed insights into the anatomy of bones, tissues, and nerve cells. These parameters are relevant for the development of implants specifically for these species,” said Keppeler.

With the data obtained on the anatomy of the different cochleae, the team was also able to design an implant with LED emitters for common marmosets and the implant was then inserted by Alexander Meyer, an experienced ear, nose, and throat surgeon, at the University Medical Center Göttingen, in a manner analogous to surgery in humans. Furthermore, the researchers used imaging data to simulate the propagation of light generated by the emitters of the optical implants in the cochlea of non-human primates.

“Our simulations indicate spatially limited optogenetic excitation of auditory neurons and thus higher frequency selectivity than with previous electrical stimulation. According to these calculations, optical cochlear implants lead to significantly improved hearing of speech as well as of music,” said Moser.

The study was conducted in cooperation between researchers from the German Primate Center – Leibniz Institute for Primate Research with the Cluster of Excellence Multiscale Bioimaging: From Molecular Machines to Networks of Excitable Cells (MBExC) and the Collaborative Research Center “Cellular Mechanisms of Sensory Processing” (SFB889) at the University Medical Center Göttingen, the University of Göttingen, and the Max Planck Institute for Experimental Medicine.

Original paper: Keppeler D, Kampshoff CA, Thirumalai A, et al. Multiscale photonic imaging of the native and implanted cochlea. PNAS. 2021;118(8):e2014472118.

Source: German Primate Center, PNAS

Images: German Primate Center, Daniel Keppeler, UMG