Research | July 2020 Hearing Review

By Anne D. Olson, PhD, David Maidment, PhD, and Melanie Ferguson, PhD

OTC and DTC hearing devices will not be confined only to the United States; they are destined to influence hearing care globally. This Delphi survey systematically identifies perceptions among hearing care professionals in the UK toward new and emerging technologies and delivery options for adults with hearing loss.

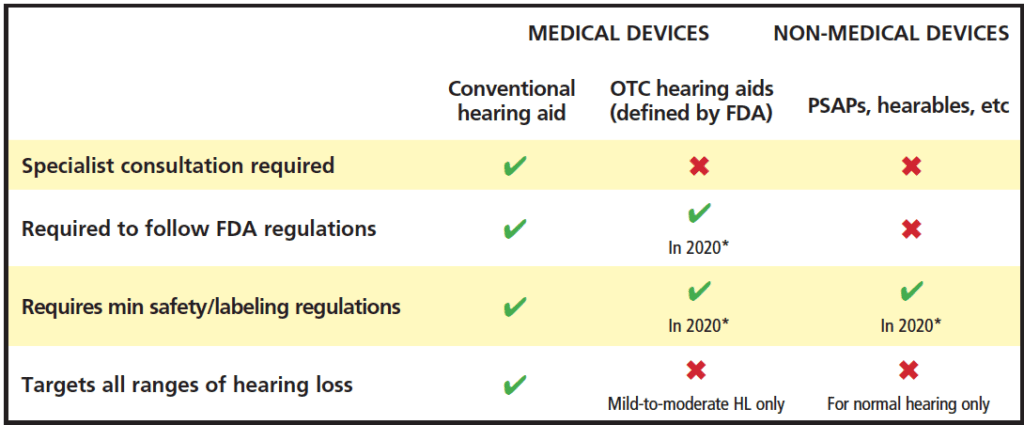

In the last decade, numerous new and emerging hearing devices for hearing loss have become commercially available and may offer more affordable and accessible approaches to address hearing loss.1,2 Examples of these devices include Personal Sound Amplification Products (PSAPs), hearables, and smartphone applications (or apps). Many new and emerging devices have some similar characteristics and functionality compared to hearing aids, however there are distinct differences. Table 1 shows a summary of selected new and emerging hearing products and features.

requirements, minimum labeling requirements, and population targeted as adapted from National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and

Medicine (NASEM).10 *FDA regulations for devices are slated for 2020, but may be delayed (see text).

In the US, since the passage of the Over-the–Counter (OTC) Hearing Aid Act of 2017,3 a new category of hearing devices was created to address those who have mild-to-moderate hearing loss. The intention of this legislation is to provide less expensive amplification options with easier access to devices so that people can self-manage their hearing loss. Forthcoming Food and Drug Administration (FDA) specifications about regulatory oversight for this category is slated for release by August 2020, although the FDA’s necessary attention to the Covid-19 pandemic may end up delaying the finalized rules (possibly into 2021).4 When released, the hope is that regulations will also be in place to regulate PSAPs appropriately.

Evidence for the Effectiveness of New and Emerging Hearing Devices

Some studies have examined the electroacoustic characteristics of PSAPs and reported that there is wide variability among devices in terms of sound quality and the extent to which they make sound audible for persons with hearing loss.5-7 Most recently, Almufarrij and colleagues8 evaluated 28 PSAPs, which were available online via Amazon, and comNpared their electroacoustic characteristics to the most widely used hearing aid model used in the publicly-funded UK National Health Service (NHS). Over half of the devices generated excessive maximum output sound pressure levels. Furthermore, the majority displayed more than a 5 dB deviation from prescribed targets in a 2cc coupler.

Other studies have examined the clinical benefits of PSAPs in people living with hearing loss. A systematic review with meta-analysis9 showed improvement in speech intelligibility in noise performance for PSAPs compared to unaided listening conditions. However, Maidment and colleagues1 in 2019 concluded that the studies identified in the review were of poor-to-fair quality and were subject to bias due to limitations in the study design.

Together, these studies highlight the need for further evidence about the efficacy of new and emerging hearing devices.

State of Play in the UK

The legislative changes in the US will have an inevitable impact on hearing healthcare delivery worldwide. In the UK, hearing aids are offered at no cost to the individual by audiologists in the NHS, which is the largest provider of hearing aids globally. While 4 out of 5 hearing aid users are seen within the NHS, an initial referral to audiology from a primary care physician is required. This step can be a key barrier to accessing services because securing a referral requires additional patient time and effort.11 Furthermore, it is estimated that only 50% of patients who would benefit from hearing aids receive an onward referral to an audiologist by their primary physician.12 While overall satisfaction with and trust in the NHS is high,13 there is also limited choice in the type of hearing aid offered to patients.14 These factors, in combination with the increased availability of new and emerging devices, could lead some individuals to seek treatment elsewhere, where greater choices are available and services are more accessible, but the financial outlay for the individual may be substantial.

It is important to consider how the increased diffusion of new technologies to address hearing loss and their associated delivery models will impact hearing care services in the UK, as well as globally. Understanding the perceptions of current hearing healthcare professionals in the UK about devices and pathways is a first step in preparing for the future. Additionally, developing a consensus from current providers about next steps in how these devices should be implemented with current patient pathways will be helpful to guide service delivery planning for hearing professionals and related stakeholders.

The purpose of this study was:

1) To systematically identify perceptions among hearing care professionals in the UK (both NHS and independent sector) toward new and emerging technologies for hearing loss, and

2) To develop a consensus toward new and emerging devices and delivery options for adults with hearing loss.

Findings from this survey may be generalizable to future plans to deliver devices either through traditional or new service delivery models in the UK.

Method

This research used a multiple round online Delphi survey.15 The Delphi methodology is a widely used approach to achieve a consensus of opinion from expert panelists. The methods used here were based on a previous electronic Delphi review16 and consisted of three rounds to minimize participant drop out.

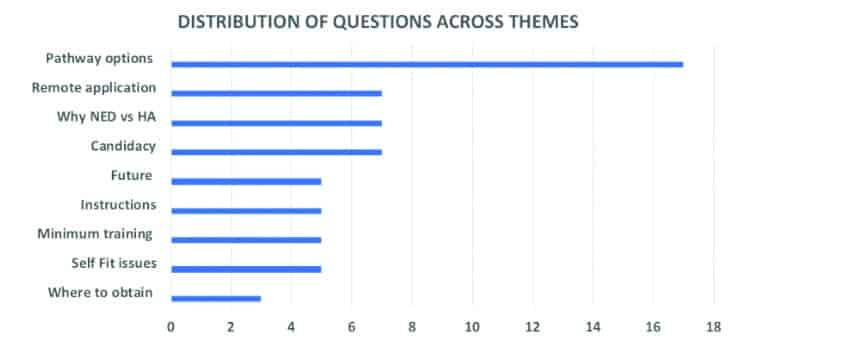

We invited UK-based NHS Audiology Heads of Service, NHS health care professionals (HCPs), as well as independent-sector HCPs during our research, which was conducted between October 2018 and March 2019. To secure an adequate number of participant responses, we recruited 34 hearing healthcare professionals who made up our expert panel. In Round 1, experts answered 9 open-response questions generated by the research team and from the results of separate focus groups of healthcare practitioners and adults with hearing loss related to new and emerging devices: 1) pathway options, 2) appropriate candidates, 3) remote applications, 4) why someone might try a new/emerging device versus a hearing aid, 5) future applications, 6) instructions, 7) minimum training requirements, 8) self-fit issues, and 9) where to obtain devices.

Written text responses to the 9 questions were coded and categorized using an established thematic analysis procedure.17 From responses in Round 1, authors generated 61 statements across 9 thematic areas (Figure 1). In Round 2, expert panelists were asked to rate statements using a 5-point Likert scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” In Round 3, statements from Round 2 were recirculated with both individual and group summary statistics. Thus, experts received both a copy of their own responses from Round 2 questions, as well as summary information about the group scores (mean rankings). Experts were instructed to review their own scores, as well as the group scores from Round 2, and then invited to rate the same 61 statements. Consensus was defined a priori as when expert panelists reached ≥80% agreement for each statement.

Results

Round 1. A total of 32 of the 34 invited experts (94%) completed the open response survey. Of these respondents, 62% (n=20) were NHS audiologists and 38% (n= 12) were independent HCPs or hearing industry experts.

Round 2. Thirty-one of the 32 experts (97%) responded to the second round of the Delphi review. At the end of Round 2, there were 35 statements (51%) that reached ≥80% agreement.

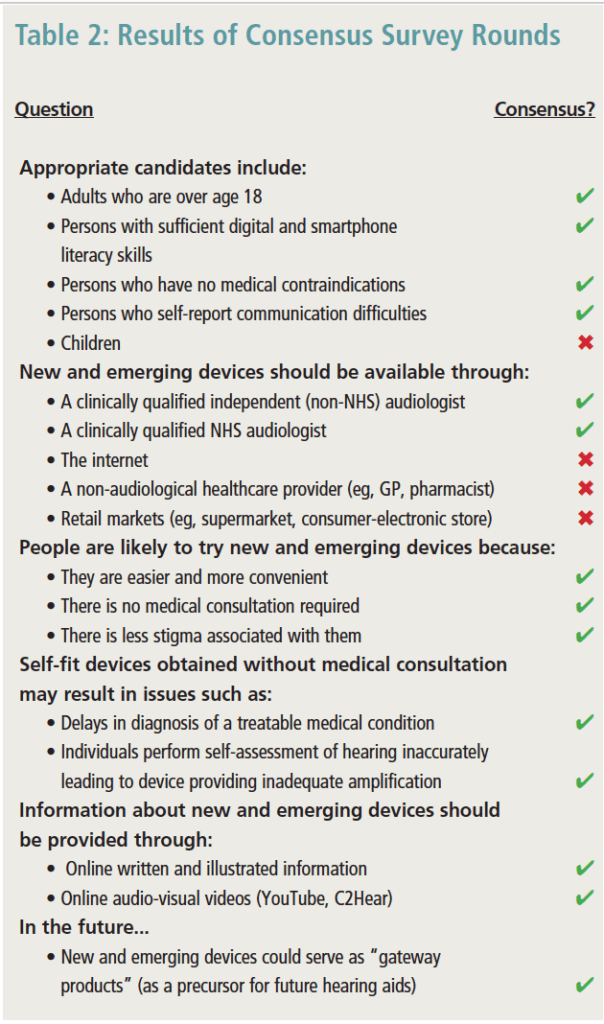

Round 3. A total of 27 of the 31 experts (87%) responded to the third round of the Delphi review. At the end of Round 3, there were 46 statements (75%) that reached ≥80% agreement. Some of these key findings arehighlighted in Table 2. Following Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, there were no statistically significant differences between NHS and independent sectors across all questions asked (p>.05). Therefore, results from both the NHS and independent groups were combined and are reported together.

did not .

In terms of candidacy for new and emerging devices, there was consensus that adults over age 18, those who report communication difficulties, and those with sufficient digital and smartphone literacy skills, along with those reporting no medical contraindications, would be ideal candidates. Fewer experts thought that devices should be available for children ages 5-18 (40%).

There was overall consensus (90%) that both NHS and independent providers should be a resource for new and emerging devices. Interestingly, there was stronger agreement (70%) about the availability of devices through the internet where there is no sales support in comparison to retail settings (59.3%) and non-audiological healthcare settings (63%).

Overwhelming agreement was observed about reasons that individuals may try new and emerging devices. They were considered to be easier and more convenient (93% agreement), did not require medical consultation (93%), and there was less perceived stigma associated with such devices in comparison to conventional hearing aids (88%).

The experts were in complete agreement about key barriers that might negatively impact outcomes as individuals pursue new and emerging devices to address hearing problems. First, they indicated that individuals using a direct-to-consumer (DTC) model without consultation of a healthcare provider will likely suffer from delays in treatment for medical conditions, such as wax or infection (100%). Second, individuals may perform a self-conducted hearing assessment incorrectly resulting in inadequate amplification (100%).

Overall, experts agreed on the content that should be provided with devices acquired without professional support. They specifically encouraged the use of both written and visual instructions (92%), along with online video tools such as C2Hear (https://c2hearonline.com) and YouTube resources (88%). In the future, experts agreed that new and emerging devices would lead to earlier intervention for hearing loss (96%) and could be considered “gateway products” (96%).

Discussion

Overall, results showed a significant shift in consensus from the second to third rounds such that experts agreed on 51% and 75% of the questions respectively. This progression of agreement demonstrates the development of consensus18 in this study. Furthermore, given that three-quarters of the questions showed ≥80% consensus, there was broad agreement in many areas. For example, there is overarching agreement on candidacy issues, the reasons people might try a new device instead of a hearing aid, on the type of information that should be provided about new and emerging devices, as well as how this information should be shared. Additionally, the experts appeared to concur on the notions about why people might try a new device rather than a hearing aid.

UK-based experts envision that the availability of these devices may improve intervention options for adults with hearing loss. They also agreed that new and emerging devices will essentially serve as “gateway products” that could ultimately lead to earlier uptake of hearing aids. The idea of gateway products has been widely discussed in relation to tobacco cessation products19 and drug use.20 However, this notion can also be applied to hearing healthcare where new and emerging hearing devices serve as a “gate” between two conditions of hearing care which would be: 1) doing nothing about a hearing loss, and 2) getting a hearing aid. The idea underlying a gateway product is that the first step has to be simple and present with minimal risk. Given that new and emerging devices are less expensive than traditional hearing aids, accessible online, and do not require professional consultation, the gateway product idea is appropriate.

Both sectors (NHS and independent sector) agreed that they should provide new and emerging devices. This is exciting because it suggests that both sectors view devices as being part of future hearing healthcare. As such, it would appear that both sectors should be actively preparing for future implementation of service models that include these products. Several of the questions in this survey could serve as a template by which to model these services.

While the experts did not reach consensus on other delivery models (ie, internet and retail), the lack of consensus may be influenced by the fact that they remain concerned about the lack of clinical support, or individual’s ability to self-fit a hearing aid.21,22 Possible solutions need to be explored.

Summary and Conclusions

The upcoming changes in US hearing aid regulation and new hearing technologies are creating disruptive circumstances for healthcare providers globally. As new and emerging devices become increasingly more available over the counter without healthcare consultation, audiologists will need to collaborate, develop, and evaluate alternative approaches to incorporate new devices into traditional practice settings.

This Delphi review has highlighted that there are many areas where this panel of UK experts is in agreement, and these can serve as a blueprint for delivery of these new and emerging devices. Both the UK NHS and independent sectors can use these findings to develop and pilot new service delivery models that meet the hearing healthcare needs of individuals. A future paper will discuss the pros and cons of obtaining devices through these alternative pathways.

References

1. Maidment DW, Ali YHK, Ferguson MA. Applying the COM-B model to assess the usability of smartphone-connected listening devices in adults with hearing loss. J Am Acad Audiol. 2019;30(5):417-430.

2. Maidment DW, Ferguson M. An application of the Medical Research Council’s guidelines for evaluating complex interventions: A usability study assessing smartphone-connected listening devices in adults with hearing loss. Am J Audiol. 2018;27(3S):474-481.

3. Warren E, Grassley C. Over-the-counter hearing aids: The path forward. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):609-610.

4. Jilla AM, Johnson CE, Danhauer JL. Disruptive hearing technologies and mild sensorineural hearing loss I: Accessibility and affordability issues. Semin Hear. 2018;39(2):135-145.

5. Chan ZYT, McPherson B. Over-the-counter hearing aids: A lost decade for change. Biomed Res Int. 2015;Article ID:827463.

6. Reed NS, Betz J, Lin FR, Mamo SK. Pilot electroacoustic analyses of a sample of direct-to-consumer amplification products. Otol Neurotol. 2017;38(6):804-808.

7. Callaway SL, Punch JL. An electroacoustic analysis of over-the-counter hearing aids. Am J Audiol. 2008;17(1):14-24.

8. Almufarrij I, Munro KJ, Dawes P, Stone MA, Dillon H. Direct-to-consumer hearing devices: Capabilities, costs, and cosmetics. Trends Hear. 2019;23:1-18.

9. Maidment DW, Barker AB, Xia J, Ferguson MA. A systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the effectiveness of alternative listening devices to conventional hearing aids in adults with hearing loss. Int J Audiol. 2018;57(10):721-729.

10. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). Hearing Healthcare for Adults: Priorities for Improving Access and Affordability. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/23446/hearing-health-care-for-adults-priorities-for-improving-access-and. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Published 2016.

11. Knudsen LV, Nielsen C, Kramer SE, Jones L, Laplante-Levesque A. Client labor: Adults with hearing impairment describing their participation in their hearing help-seeking and rehabilitation. J Am Acad Audiol. 2013;24(3):192-204.

12. Davis A, Smith P, Ferguson M, Stephens D, Gianopoulos I. Acceptability, benefit and costs of early screening for hearing disability: A study of potential screening tests and models. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11(42):1-294.

13. Zhao D, Zhao H, Cleary PD. International variations in trust in health care systems. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2019;34(1):130-139.

14. Bisgaard N, Ruf S. Findings from EuroTrak surveys from 2009 to 2015: Hearing loss prevalence, hearing aid adoption, and benefits of hearing aid use. Am J Audiol. 2017;26(3S):451-461.

15. Hsu C-C, Sanford BA. The Delphi technique: Making sense of consensus. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation. 2007;12(10):1-8.

16. Ferguson M, Leighton P, Brandreth M, Wharrad H. Development of a multimedia educational programme for first-time hearing aid users: A participatory design. Int J Audiol. 2018;57(8):600-609.

17. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77-101.

18. Holey EA, Feeley JL, Dixon J, Whittaker VJ. An exploration of the use of simple statistics to measure consensus and stability in Delphi studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:52.

19. Etter J-F. Gateway effects and electronic cigarettes. Addiction. 2018;113(10):1776-1783.

20. Otten R, Mun CJ, Dishion TJ. The social exigencies of the gateway progression to the use of illicit drugs from adolescence into adulthood. Addict Behav. 2017;73:144-150.

21. Convery E, Keidser G, Seeto M, McLelland M. Evaluation of the self-fitting process with a commercially available hearing aid. J Am Acad Audiol. 2017;28(2):109-118.

22. Keidser G, Convery E. Self-fitting hearing aids: Status quo and future predictions. Trends Hear. 2016;20:1-15.

Correspondence can be addressed to HR or Dr Olson at: [email protected].

Original citation for this article: Olson AD, Maidment D, Ferguson M. Consensus on the use of emerging hearing devices and service delivery models in the UK. Hearing Review. 2020;27(7):19-21.