By Heidi Douglass, Communications & Projects Officer, Centre for Healthy Brain Ageing (CHeBA)

In Australia, hearing loss affects 74% of people aged over 70. International studies estimate that people with severe hearing loss are five times more likely to develop dementia. Addressing midlife hearing loss could prevent up to 9% of new cases of dementia – the highest of any potentially modifiable risk factor identified by a commissioned report published in The Lancet in 2017.

Related article: 2020 ‘Lancet’ Commission Report Finds Untreated Hearing Loss in Midlife as ‘Largest Modifiable Risk Factor’

A research collaboration between the Centre for Healthy Brain Ageing (CHeBA), UNSW Sydney, and Macquarie University’s Centre for Ageing, Cognition and Wellbeing has confirmed significant associations between self-reported hearing loss and cognition, as well as increased risk for mild cognitive impairment or dementia. An article detailing the results appears on CHeBA’s website.

The research, published in Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition used data from 1,037 Australian men and women aged 70-90 years enrolled in CHeBA’s Sydney Memory & Ageing Study from 2005-2017.

Individuals who reported moderate-to-severe hearing difficulties had poorer cognitive performances overall, particularly in the domains of Attention/Processing Speed and Visuospatial Ability. They also had a 1.5 times greater risk for MCI or dementia at the 6 years’ follow up.

While hearing loss was independently associated with a higher rate of MCI it did not show this in people with dementia. This likely resulted from the number of people with dementia at six years’ follow-up being too small to demonstrate a statistically significant effect.

Lead author at Macquarie University’s Department of Cognitive Science, Dr Paul Strutt, said the findings provide new hope for a means of reducing risk of cognitive decline and dementia in individuals with hearing loss.

“The presence of hearing loss is an important consideration for neuropsychological case formulation in older adults with cognitive impairment,” said Strutt. “Hearing loss may increase cognitive load, resulting in observable cognitive impairment on neuropsychological testing.”

Co-Director of CHeBA and co-author, Professor Henry Brodaty, said the study was the first of its kind to identify the relationship between hearing loss and risk for mild cognitive impairment or dementia in a large Australian-based study of older adult men and women.

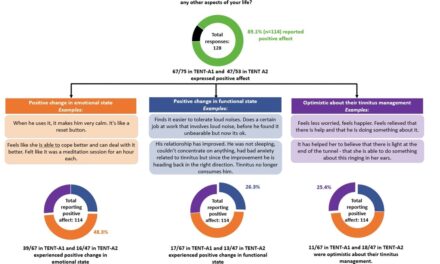

“The findings contribute to the evidence base providing support for a study looking at the effect of hearing devices on cognitive function,” said Brodaty. “Studies are now emerging that hearing aids may reduce this risk. Large, multi-center trials examining the wide-ranging benefits of hearing interventions in older adult populations with hearing loss could determine the potential for risk reduction associated with this significant and modifiable risk factor for MCI and dementia in older age.”

CHeBA’s Sydney Memory and Ageing Study is an observational study of older Australians that commenced in 2005 and researches the effects of aging on cognition over time.

Original Paper: Strutt PA, Barnier AJ, Savage G, et al. Hearing loss, cognition, and risk of neurocognitive disorder: Evidence from a longitudinal cohort study of older adult Australians. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13825585.2020.1857328.

Source: CHeBA; Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition