Why hearing care professionals and physicians need to fight diabetes together

Researchers examining the link between hearing loss and lifestyle factors believe that hearing healthcare has an important role in diabetes care and management. And now the American Diabetes Association, the CDC, and others are starting to agree…

Research | May 2021 Hearing Review

By Lena Kauffman

A patient you are attending to is older and obviously overweight. It is warm outside, so he sips on a large Coke from McDonalds (80 grams of sugar, 290 calories). Taking a brief patient history, he mentions that his doctor says he needs to lose weight and has warned him about diabetes. What do you do next?

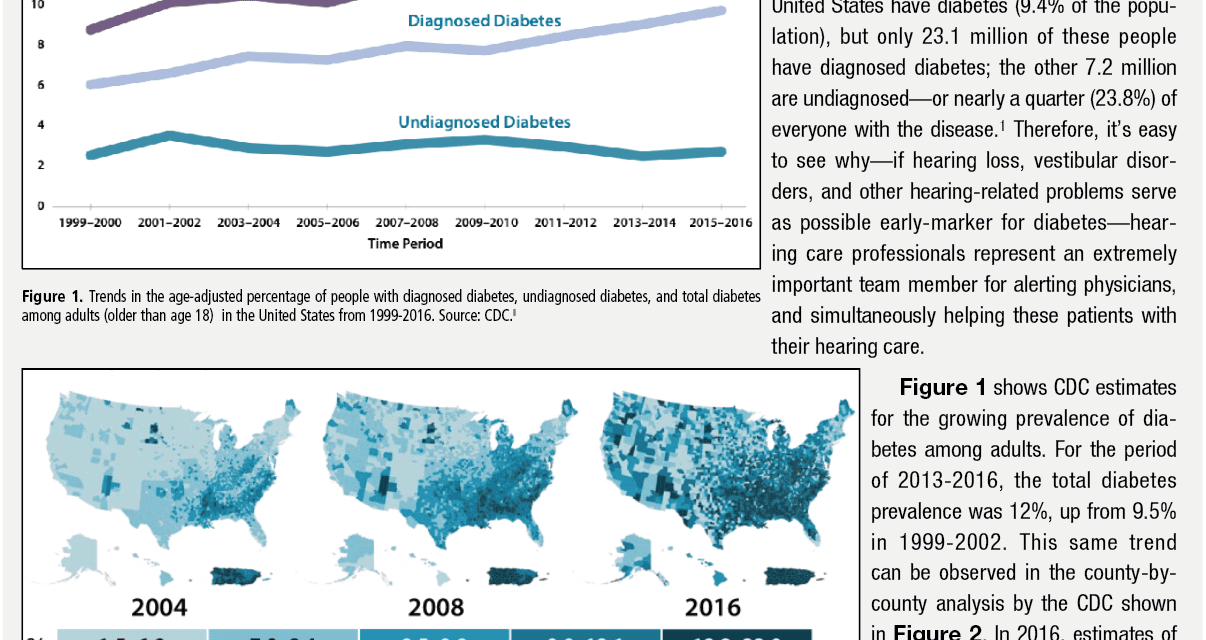

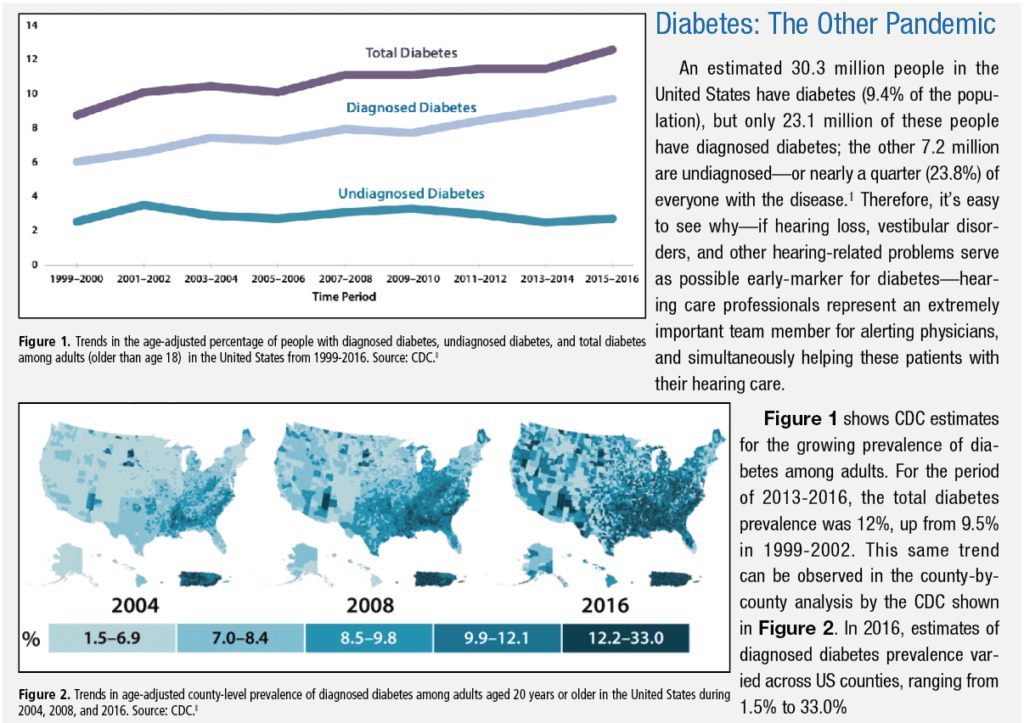

Simply looking at the numbers, it is clear that audiologists are seeing a lot of patients who have diabetes and prediabetes. More than 34 million people (about 1 in 10 US residents) have diabetes and another 88 million (a third of the population) have pre-diabetes, estimates the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).1 The prevalence increases with age. CDC statistics indicate that more than 1 in 4 people over age 65 now have diabetes.

Like diabetes, hearing loss is very prevalent. About 15% of American adults (37.5 million) report trouble hearing and the incidence increases with age. Nearly 25% of those ages 65 to 74 and 50% of those who are 75 and older have disabling hearing loss.2 There is a great deal of overlap between the two groups.3 According to the American Diabetes Association, hearing loss is twice as common in people with diabetes as it is in those who don’t have the disease. Additionally, US patients with prediabetes blood glucose levels have been found to have a rate of hearing loss that is 30% higher than in those with normal blood glucose levels.4

Yet, despite this overlap, there are currently no special clinical guidelines for how audiologists should approach treating these patients, and audiologists are not included in the CDC’s PPOD (Pharmacy, Podiatry, Optometry, and Dentistry) effort to recruit more providers in educating patients with diabetes about their condition and initiating appropriate referrals when necessary.

Importantly, however, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) has now recognize hearing loss as being more common in people with diabetes, adding audiology to its table on referrals for initial diabetes care management in its January 2021 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2021.5 It has also added a paragraph on “Sensory Impairment” (page S49) which reads, in part:

Hearing impairment, both in high-frequency and low- to midfrequency ranges, is more common in people with diabetes than in those without, with stronger associations found in studies of younger people. Proposed pathophysiologic mechanisms include the combined contributions of hyperglycemia and oxidative stress to cochlear microangiopathy and auditory neuropathy. In a National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) analysis, hearing impairment was about twice as prevalent in people with diabetes compared with those without, after adjusting for age and other risk factors for hearing impairment. Low HDL cholesterol, coronary heart disease, peripheral neuropathy, and general poor health have been reported as risk factors for hearing impairment for people with diabetes, but an association of hearing loss with blood glucose levels has not been consistently observed. In the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (DCCT/EDIC) cohort, time-weighted mean A1C was associated with increased risk of hearing impairment when tested after long-term (.20 years) follow-up…5

An organization that lobbied for this new addition is The Audiology Project (TAP), which has been gathering research and advocating for clinical audiology guidelines for patients with diabetes. Kathy Dowd, AuD, founded TAP in 2016 after a personal experience caring for a family member with diabetes made her realize that many patients newly diagnosed with diabetes are never referred for a hearing screening even though the link between diabetes and increased risk of hearing loss has been observed for decades.

In her own practice, Dowd had made a point of encouraging the referral of patients with chronic disease for hearing screening because it seemed obvious that medications and diseases that impacted the whole body would also impact the auditory system. However, she had no evidence-based national guidelines to follow for this work.

“I just knew that diabetes was a chronic disease that caused hearing problems,” Dowd recalls. “I probably could have counseled them much better with guidelines.”

Advocacy efforts by TAP and others are now gaining steam. For example, in April 2021, a 90-minute webinar7 was presented by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Division of Diabetes Translation (DDT) in which The Audiology Project featured a panel of experts who spoke about the relationship between diabetes and ear health, and the CDC has published “Take Charge of Your Diabetes: Healthy Ears” (see p 12).

Does Diabetes Cause Hearing Loss?

One challenge advocates for clinical guidelines for the care of patients with diabetes in the audiology setting face is that, while there are several strong theories about how diabetes can harm hearing and vestibular function, the anatomy of the ear complicates the research. Specifically, the tiny and delicate structures of the ear make the type of dissection and medical imaging studies done to observe the impact of diabetes in other organs and systems of the body next to impossible in the inner ear. In medical illustrations, the cochlea may appear as a structure you can touch and hold, but it is more like negative space inside the temporal bone, explains Victor Bray, PhD, associate professor at Salus University Osborne College of Audiology. Bray’s research interests include the comorbidities of hearing and vestibular disorders, and the issue of not being able to easily open up the inner ear and observe what happens inside the cochlea of a living person is a vexing one.

“You have to have the animal models to do the dissection to see where the damage is, and then you have to project what that possibly means for humans,” Bray explains. “So a lot of the science relies on inference, and this makes [hard conclusions] very difficult.”

However, most studies do show a strong correlation between diabetes and hearing loss, and the science points to three main ideas for how diabetes either directly or indirectly can harm the auditory system. The first is that high blood glucose levels can cause tiny blood vessels in the inner ear to break, disrupting sound reception. The inner ear has the smallest blood supply of any organ in the body, and diabetes is a disorder that heavily impacts the capillary system. The second theory is that diabetes damages the nervous system and can harm the delicate nerves carrying information to the central auditory system in the brain. The third is that many medications patients with diabetes take are ototoxic. The TAP website lists 75 medications that may be prescribed for patients with diabetes, many of which are known to impact hearing and/or vestibular function. All three factors may be at play, but teasing out the role of each and separating the diabetes factors from other factors causing hearing damage over a lifetime is tricky.

Christopher Spankovich, AuD, PhD, MPH, is an associate professor and vice chair of research for the Department of Otolaryngology and Communicative Sciences at the University of Mississippi Medical Center. His laboratory examines pathophysiology of acquired forms of hearing loss and tinnitus with the goal of identifying novel approaches for prevention. To him, diabetes is a clear area where there is potential to mitigate and reduce the severity of hearing loss by both preventing the development of diabetes through lifestyle changes and, in patients with diabetes, counseling. In particular, these patients should understand they are at higher risk for hearing loss and can prevent further damage to their ears by managing their diabetes and reducing exposure to other hearing loss risk factors. For example, a person with diabetes might want to be extra-diligent about wearing ear protection when they are in loud places—the same way a person with very light skin needs to be extra-diligent about wearing sunscreen.

“There have been studies that have looked at hearing loss, age, and the role of diabetes, and indeed most of those studies support that there is an independent role of diabetes and susceptibility to hearing loss with age,” Spankovich says. “But when some studies have looked only in older individuals, they find that, in the oldest of those older individuals, there’s not necessarily a significant difference between those who have diabetes and those who do not. At that point [of age], so many of the different variables start playing a role that it sort of dilutes the ability to identify the role of diabetes in compromised hearing. However, when researchers look at the younger groups—people in their 30s and 40s—we do see the significant difference between individuals with diabetes compared to individuals without diabetes and hearing loss.”

For example, a 2008 study by Bainbridge and colleagues6 looked at over 5,140 people ages 20 to 69 who were in the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics survey and found that, for low- and mid-frequency hearing impairment, prevalence was 21% among 339 adults with diabetes compared to 9.4% among 4,741 adults without diabetes. For high-frequency hearing impairment, prevalence was 54.1% among those with diabetes compared to 32% for adults without diabetes.

Hearing Status as the “Canary in the Coal Mine” of Chronic Disease

While it would certainly support the development of clinical guidelines to have an experimental study that documents diabetes causing hearing loss in humans the way diabetic retinopathy has been observed to cause blindness, in another sense, it is beside the point. We already know many patients with hearing loss and vestibular disorders have diabetes. This alone makes it important for audiologists to consider how these patients should be treated.

Bray calls the cochlea the “canary in the coal mine” of chronic disease because it will start to show damage before larger and less delicate systems with more backup circulation are impacted. Spankovich’s lab is even studying if otoacoustic emission (OAE) tests that measure inner-ear function could identify patients at risk for cardiovascular disease later in life. This means that if audiologists and other hearing care professionals want to be serious about the health of patients, they need to ask questions about why the patient’s hearing has been harmed in the first place. Then, when warranted, the clinicians can refer patients back to their doctors for additional investigation.

“Sometimes what happens in the ear happens there before it happens in other parts of the body,” Bray says.

Diabetes patients may be a good example of this. According to CDC estimates, 1 in 5 people with diabetes do not know they have it.1 If a hearing care professional suspects a patient has undiagnosed diabetes or some other chronic disease contributing to their hearing loss and does not encourage that patient to go to a doctor and get further testing, the clinician may be missing an important opportunity to protect that patient.

“I’m not suggesting that audiologists start to diagnose other diseases or anything at all like that,” Bray says. “But I do think the next step for our profession is to start thinking of whole-body health, and also thinking of the ear, hearing, and especially the status of the cochlea as an early indicator of health that is tied to whole-body health. And when we see unusual hearing loss, notice that it is likely happening for a reason, and not diagnose but carefully refer when appropriate.”

Diabetes as Part of Value-Based Hearing Healthcare

For hearing care professionals, it is not just that there is a high rate of comorbidity between diabetes and hearing loss. Having both conditions could lead to a poorer overall prognosis for your patient’s health status and higher costs for the healthcare system overall. That means audiology and hearing healthcare in general can play an important role in making diabetes care (and hearing health) more valuable to patients and health systems alike.

On a basic level, having both diabetes and hearing loss can complicate the patient’s ability to maintain a hearing aid. Richard Gans, PhD, a leading researcher on vestibular disorders and former president of the American Academy of Audiology, notes that diabetic retinopathy and neuropathy is highly prevalent in patients with diabetes. Hearing aids and hearing aid batteries are tiny, and simply changing a battery in a hearing aid can be a frustrating or even impossible task for someone with poor vision, poor sense of touch, or both, Gans explains. Audiologists want patients to succeed in using their hearing aids, and the odds of this can be improved by simply discussing with the patient how diabetes can complicate hearing aid use and maintenance. He says hearing care professionals can devise a plan and select hearing aids to help patients overcome these physical limitations.

Hearing care clinicians can also reinforce the messages of other healthcare providers about the importance of following the diet, lifestyle, and medication regimens prescribed for them in managing their diabetes. While not officially part of the CDC’s effort to extend diabetes education through PPOD providers, the tools advocated for PPOD providers—like developing key messages for patients with diabetes and how to create collaborative care with other specialties—is applicable to audiology as well. (The PPOD guide for providers is available free online at: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/ndep/pdfs/working_together_to_manage_diabetes_webinar_slides.pdf)8

Bray believes it is critical for hearing care professionals to begin raising awareness about the linkages between chronic conditions, hearing loss, and negative outcomes with referring physicians. By showing the doctor the progression of the patient’s hearing loss and also demonstrating effective ways to communicate with that patient—who is also the audiologist’s patient—the audiologist becomes a natural extension of the diabetes care team.

“If we can get [physicians] to start being aware of hearing loss in patients who have this condition, they can start using these strategies and refer patients back to audiologists for evaluation and consideration for management, and then we are closing the loop,” Bray says. “That’s where the growth opportunity for audiology practices is occurring as you become part of the medical system: referring patients appropriately and the recognition on the other end that maybe they need to refer patients back to you. If we could see those patients earlier and start working with them earlier, they would be better off, they would find more success with amplification, and our practices and profession would be better off.”

Hearing Care Improves Health, Patient Communication and Compliance, and Reduces Costs for People with Diabetes

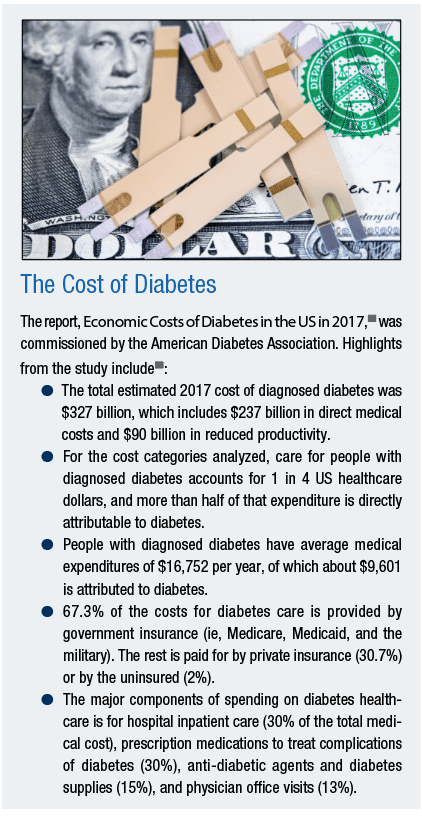

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, diabetes was the seventh leading cause of death in the United States, with total direct and indirect estimated annual costs at $327 billion. In 2017, excess medical costs per person associated with diabetes was $9,601 (both total annual costs and per-person costs in 2017 dollars).1 That same year, Medicare launched its Diabetes Prevention Program model with the hope that preventing new cases of diabetes and keeping Medicare beneficiaries healthier could save the government more than $180 million annually.9

Similarly, hearing loss has been identified as a cost driver. A 2019 JAMA study10 found persons with untreated hearing loss also experienced more in-patient stays and were at greater risk for 30-day hospital readmission. This translated to healthcare costs that were 46% higher for those with untreated hearing loss. One theory for why this happens is that hearing loss makes clear communication difficult, and poor communication is linked to medical errors and non-compliance issues in patients managing chronic conditions, like diabetes.11

“Communication is critical to our wellbeing and our interaction with family and friends and also our interaction with our healthcare providers,” Spankovich says. “Hearing loss can create compromised communication, and that can lead to errors such as a patient mishearing what a recommendation is from their provider in terms of what they should be doing for X, Y, and Z. This in turn can lead to greater issues with any type of morbidity related to whatever disorder they have.”

Audiologists and hearing care professionals can advise on improving communication, Bray says, and this is even more important in an era when telemedicine is being rapidly adopted nationally to facilitate contact-less virtual medical appointments. On May 1, 2020, CMS announced that in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, it was broadening the list of services that could be provided to Medicare patients by phone to include many behavioral health and patient education services, like diabetes self-management education. At the same time, CMS also announced that it would be increasing payments for these telemedicine visits to “match payments for similar office and outpatient visits.”12 But even on video calls, patients with hearing loss can struggle to follow what is said.

Hearing care professionals can guide these patients to a variety of adaptive technologies to help them communicate with their diabetes management team and avoid medical errors through accidental miscommunications. “Oftentimes, hearing loss is perceived as less important than other chronic conditions, but I think there is a wealth of evidence13 that shows hearing and communication are inextricably tied to physical and mental health,” says Dave Blanchard, Strategic Business Development Manager for Hamilton® CapTel®, a captioned telephone provider. “Eliminating barriers through the use of available technology, such as a captioned telephone, allows individuals with hearing loss to connect directly with physicians, as well as stay in touch with family and friends. Staying connected can be a critical factor in staying healthy and maintaining independence.

“Like the old game of ‘telephone,’ messages passed through numerous people increases the odds that something will be miscommunicated,” adds Blanchard. “A captioned telephone can help a patient with diabetes and hearing loss connect directly with their care providers, and may reduce the odds of miscommunication.”

Flagging speech-understanding problems for other clinicians is also valuable. During personal interactions, speech understanding relies on both visual and auditory clues. Today’s enhanced infection-control practices—such as doctors wearing medical masks and sitting farther away during an appointment—make it harder for even people with normal hearing to clearly understand what is being said. Masks can significantly distort the sound of spoken words, causing speech to become inaudible and completely remove the visual clues needed for lip-reading.14

“Our eyes and our ears actually are neurologically linked together to help us understand what people are saying to us,” Bray says. “When you take away the visual cues, speech recognition abilities go down. There’s no doubt about that. Even for normal-hearing people, the wearing of a mask will take away cues that are important for speech understanding.”

Some companies have already developed masks with clear sections in the center that allow for lip-reading, and this trend could be beneficial for other clinicians serving patient populations at higher risk for hearing loss, like people with diabetes. As Bray points out, the interventions need not be high tech. Audiologists can recommend fairly simple things, like primary care providers and diabetes educators just carrying a pocket amplification device with them. However, without an audiologist as part of the diabetes care team, these simple recommendations—practical solutions for improving patient understanding, which in turn enhances the patient’s ability to manage their own diabetes—may be overlooked.

Diabetes and Falls

Another important role audiologists may play in reducing the overall costs of care for patients with diabetes while simultaneously improving outcomes is addressing vestibular concerns that can come with damage to the inner ear due to diabetes. Dr Gans has pointed out in articles and workshops going back more than two decades that dizziness is the number-one complaint among people over age 70, and that the audiologist is best positioned to serve as the gatekeeper for the dizzy patient.15

A 2017 meta analysis found that, across 12 studies, patients with type 2 diabetes were at increased risk for fractures from low-energy falls.16 These falls are ones that occur from standing height, such as might occur if you trip or get dizzy and fall over. Researchers have found vestibular dysfunction to be 2.3 times more likely in those with diabetes than in those without it.17 However, over time, the body can often compensate with visual cues or the sense of touch, Spankovich notes. Unfortunately, diabetes is a disease that attacks all the body’s sensory systems at once. Vision may be blurred from diabetic retinopathy. Sensation from the feet may be muted by diabetic neuropathy. And on top of all of that, the patient may experience dizziness from fluctuations in blood-sugar levels (hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia) and medications.

“Our balance system is susceptible to the perfect storm of diabetes,” Spankovich says. “You have an individual who has multiple systems that have been impacted, which greatly minimizes the ability of the brain to compensate.”

Because newer risk-sharing reimbursement arrangements like accountable care organizations may put health systems and hospitals at increased financial risk if a patient suffers a serious fall, there is great interest in methods to identify patients at increased risk of falls and other bad outcomes.11 Audiologists can help with this, Bray believes, by improving awareness of how diabetes can damage the vestibular system as well as hearing.

Insurers likewise are eager to reduce the odds of falls and complications from poorly controlled diabetes. Dowd noted that one major North Carolina insurer had already expressed interest in a protocol TAP was examining, where pharmacists might administer a basic hearing health screening test on an iPad to patients with diabetes at the same time as they screen for other diabetes complications by checking feet and gums.

“As an audiologist, I would have no problem having somebody else screening hearing,” Dowd says. “I just want to make sure they get follow-up in a year and a referral for audiology testing if they fail the screening.”

Next Steps in Diabetes Care

While researchers continue to study the ways diabetes may harm the auditory system, TAP is hard at work compiling studies that could lead to the writing of clinical guidelines for audiologists, as well as raising awareness. Dowd encourages anyone interested in helping to visit the TAP website (theaudiologyproject.com) and get in touch with the organization for resources to educate their local medical community. Although audiology is a small field, for a disease like diabetes where both incidence and costs are rising, it could make an important contribution and simultaneously create a larger role for hearing care professionals and additional patient referrals.

Researchers agree. “As audiologists, we are very ear-centric,” Spankovich concludes. “We are focused on the ear and we are focused on balance as related to the ear. And that’s great. I love the ear. It is this complex, amazing thing. But people have to remember that the ear is connected to a head, which is connected to an entire body, and the health of that entire body is going to influence the integrity of that ear. These are not separate things. And so, really, to best take care of your patients, it’s not simply just identifying the hearing loss and fitting them with amplification and counseling them by providing more rehabilitation strategies. It’s more than that. We also want to potentially slow the progress of the hearing loss that they do have, and provide strategies to prevent the hearing loss in the first place.”

Acknowledgement

This article is adapted and updated by HR from a special report sponsored by Hamilton® CapTel® published online by The Hearing Review in June 2020.20 Hamilton is a registered trademark of Nedelco, Inc. d/b/a/ Hamilton Telecommunications. CapTel is a registered trademark of Ultratec, Inc.

Visit the Audiology Project at: www.theaudiologyproject.com.

Citation for this article: Kauffman L. Diabetes and hearing loss. Hearing Review. 2021;28(5):14-18.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National diabetes statistics report, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/features/diabetes-stat-report.html. Published/Updated February 11, 2020.

2. National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD). Quick statistics about hearing. https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/statistics/quick-statistics-hearing. Published/Updated March 25, 2021.

3. Abrams H. Hearing loss and associated comorbidities: What do we know? Hearing Review. 2017;24(12):32-35.

4. American Diabetes Association. Diabetes and hearing loss. https://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-and-hearing-loss.

5. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes–2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44[Suppl 1]:S1-S2.

6. Bainbridge KE, Hoffman HJ, Cowie CC. Diabetes and hearing impairment in the United States: Audiometric evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999 to 2004. Ann Int Med. 2008;149(1):1-10.

7. Down K, Gaffney P, Spankovich C, Piker EG, Ballard AM. The impact of diabetes on hearing and balance [webinar]. April 7, 2021. https://www.theaudiologyproject.com/latest-news/2021/4/7/free-cdc-webinar-the-impact-of-diabetes-on-hearing-and-balance.

8. Frisch D, Allweiss P, Leal S, La Fontaine J, Chous P, Furnari W. Working together to manage diabetes: A toolkit for Pharmacy, Podiatry, Optometry, and Dentistry (PPOD) [webinar]. August 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/ndep/pdfs/working_together_to_manage_diabetes_webinar_slides.pdf.

9. Verma S. CMS encourages eligible suppliers to participate in expanded Medicare diabetes prevention program model. Harbor Healthcare Consultants website. https://harborhealthcare.com/cms-encourages-eligible-suppliers-to-participate-in-expanded-medicare-diabetes-prevention-program-model/.

10. Reed NS, Altan A, Deal JA, et al. Trends in health care costs and utilization associated with untreated hearing loss over 10 years. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(1):27-34.

11. Kauffman L. Special report: Hearing and Value-based Healthcare. Hearing Review. https://hearingreview.com/hearing-loss/health-wellness/special-report-hearing-care-value-based-reimbursement-medicine. Published March 3, 2018.

12. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Trump administration issues second round of sweeping changes to support US healthcare system during COVID-19 pandemic [Press release]. Apr 30, 2020.

13. Vercammen C, Ferguson M, Kramer SE, et al. Well-hearing is well-being. Hearing Review. 2020;27(3):18-22.

14. Goldin A, Weinstein B, Shiman N. How do medical masks degrade speech perception? Hearing Review. 2020;27(5):8-9.

15. Gans R. Rethinking treatment of dizzy patients and balance disorders. Hearing Review. 1999;6(4):8-12.

16. Jia P, Bao L, Chen H, et al. Risk of low-energy fracture in type 2 diabetes patients: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28:3113-3121.

17. Agrawal Y, Carey JP, Della Santina CC, Schubert MC, Minor LB. Diabetes, vestibular dysfunction, and falls: Analyses from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Otol Neurotol. 2010;31(9):1445-1450.

18. American Diabetes Association (ADA). Economic costs of diabetes in the US in 2017. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(5):917-928.

19. American Diabetes Association (ADA). The cost of diabetes. https://www.diabetes.org/resources/statistics/cost-diabetes.

20. Kauffman L. Hamilton CapTel. Diabetes and hearing loss. https://hearingreview.com/resource-center/featured-reports/diabetes-hearing-loss. Published June 5, 2020.

Hamilton is a registered trademark of Nedelco, Inc d/b/a/ Hamilton Telecommunications. CapTel is a registered trademark of Ultratec, Inc.