Practice Management| September 2020 Hearing Review

Five ways to elevate your practice while preparing for the future era of OTC devices

Audiologists and other hearing care providers are rapidly finding themselves in an era of “self-serve” hearing care. These new times afford us all an opportunity to examine how we practice and begin to incorporate improved means of addressing the hearing needs of our patients. While many professionals are moving toward greater adherence to best-practice guidelines to better serve their patients and to differentiate their practices from the competition, others find needed changes more difficult to implement. This article looks at 5 easy steps practitioners can take to better align their services with best-practice guidelines and improve the hearing care outcomes of their patients—while simultaneously setting themselves above the competition and creating success levels that surpass what consumers can achieve on their own.

By John Greer Clark, PhD

Over the years, audiologists have seen patients in their offices who ostensibly arrived seeking guidance and help, but who have failed to follow professional recommendations and have left without purchasing hearing aids. We often hear our patients say, “I’m just shopping right now. I have a few other places to check with.” Or they might say, “This is a lot to think about. Let me talk with my spouse and we’ll see if we can do this right now.” Other times, we have seen patients purchase hearing aids only to subsequently return them in the first 30 days as these patients struggled to recognize the same degree of difficulties arising from their hearing loss that their friends and family were all too painfully aware of.

While the majority of the patients we see are psychologically set to move forward with our recommendations, not all are. There certainly are means for hearing care professionals (HCP) to identify the root causes of patient hesitation and ways to address concerns and heighten levels of internal motivation so that we and our patients can meet with greater successes.1-3 But clearly, change is difficult for many.

Change is Difficult, and Self-Change is the Most Difficult of All

Change is not only difficult for our patients, it is difficult for us as well. In more than 25 years in private practice, I found areas in which I became complacent. Knowing better, I continued with some practices that I knew were not ideal, but they were convenient, and (at least on the surface) seemed satisfactory.

In graduate school I learned the value and importance of using recorded speech audiometric materials.4,5 But the use of recorded tests was not demonstrated in my practicum sites and at the time it was awkward with reel-to-reel tape recordings. When I graduated and cassette tapes became more prevalent, my live-voice testing techniques were seemingly perfected and well ingrained into my practice habits. And, as I told myself, I was the one testing my patients on their initial test and subsequent tests. I did not have to worry so much about inter-test variability.

I remember a patient who had temporarily moved out of town to assist her ailing mother. While out of town she had seen another audiologist for a hearing aid problem and had been given an updated hearing evaluation. She had her medical files with her including a past audiogram and was told by the audiologist that her speech understanding had dropped by 20%. Her concerns about this heightened as the months passed. When I retested her, all was fine; I explained that the other audiologist was female and the score attained with her voice simply was not as good as that attained with mine. I remember the incredulous look on her face as she asked, “Isn’t there some way these tests can be standardized from place to place? Maybe with recordings or something?”

And, that’s when I changed my speech audiometric practices. I knew I could do better, and I began an introspective journey to be the best that I could be.

Almost all audiologists entered practice with the goal to help others improve their lives by lessening the impact of diminished hearing. That is the goal that drives us daily. We want the best for our patients.

But if we really look honestly at some of the clinical habits we maintain, and the manner in which we practice, we may find one or more areas we could change—and in the process meet our goal for our patients even more successfully. Change is difficult. But personal and professional growth is often not possible without change, and the changes that we make are often what set us apart from our competition and differentiate us in the rapidly evolving hearing aid procurement landscape.

Let’s look at five areas that research shows are ripe for clinical change for many HCPs. Every one of us should look at each of these, and possibly other areas, to see how we are doing. Some of us are doing well in all areas. Some of us may be falling short in a few. But knowing the high esteem that we all hold for the patients we serve, and the strong desire to achieve our goal of improving lives, where areas for improvement are recognized, we will each find the strength to change what we need to change. At the end of this article, we’ll look at a few strategies to help create change.

#1) Audibility

The first area we might want to look at is speech audibility. Are we restoring the audibility of speech as well as we could? No matter how impressive today’s hearing aid sound processing algorithms become, or how much further research takes us in the future, the key to any audiologic rehabilitation is restoration of the greatest degree of signal audibility. As such, the cornerstone of hearing loss management will always be the proper selection and fitting of hearing instrumentation.

We all know that hearing aids do not fully restore audibility. It is likely that our patients, at some level, are aware of this also. But often we do not fully discuss this limitation with more than a statement such as, “I wish I could restore your hearing to what it was 20 or 30 years ago, but unfortunately technology can’t do that.”

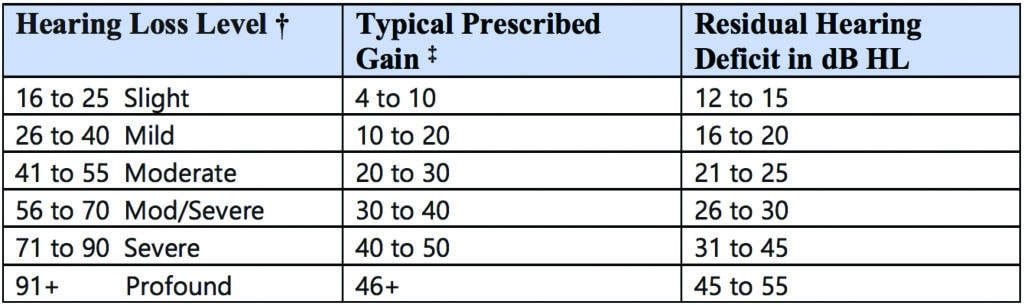

Due primarily to the physiologic sound tolerance of the impaired cochlea, hearing aids are only capable of restoring about 50% of lost hearing.6 Table 1 shows this frequently glossed-over limitation of hearing aid amplification.As this table depicts, anyone with greater than a moderate hearing loss continues with at least a mild hearing deficit even with the best of hearing aids. Similar audibility deficits remain with cochlear implantation.

† Hearing loss levels in dB HL based on 3-frequency PTA using Goodman8 descriptors as modified by Clark.7

‡ Gain based on sensory/neural hearing loss. Conductive and mixed hearing losses will tolerate more gain and result in less residual deficit.

Adapted with permission from Clark and English.2

The impact of this residual deficit is clearly apparent when we consider the frequent reports from students who undertake class assignments to wear foam earplugs for a day to experience diminished hearing. When wearing earplugs, these students with normal hearing have only an approximate 20 dB loss of sensitivity. With their ear plugs they have a pure conductive loss and do not experience the same cochlear distortions that most of our patients may be experiencing to varying degrees. Yet, students report that living with diminished hearing for a single day leads to greater fatigue, frustration for both the student and interacting family members and friends, and even voluntary withdrawal from activities they might have enjoyed.

If the results of repeated practice surveys are accurate, the manner in which many audiologists practice today does not ensure a proper hearing aid fitting and optimal signal audibily.9-12 This would be change area number 1. It does indeed seem daunting to begin to verify each hearing aid fitting through probe-mic measures. However, those who perform these measures routinely find that they quickly become proficient in their administration and that time is saved on the back end with fewer post-fitting adjustments. In addition, while on initial inspection adding probe-mic measures to one’s practice appears to be a costly enterprise, the drop in returns for credit often seen when audibility is optimally restored quickly offsets the initial purchase expense of probe-mic equipment.

#2) Our Approach to Evaluation

A second area we should change is our approach to evaluating patients for hearing aid use. As hearing aids are rapidly becoming a commodity that many individuals with mild-to-moderate hearing loss will begin to obtain without the services of an audiologist, the imperative to broaden the assessment and treatment services that we provide comes into greater focus. In 2007, Sweetow13 recommended that we move away from a generic hearing aid evaluation toward a more comprehensive Functional Communication Assessment (FCA) that includes measures that identify those needing more than hearing aids alone.

The assessment aspects of the FCA would include subjective measures of hearing loss impact and discussion of this impact; consideration of life-style communication dynamics; and exploration of cosmetic desires, cognitive status and manual dexterity. In addition, the FCA would include objective measures of hearing in noise and acceptable noise levels. This more comprehensive assessment process—billable under an itemized billing structure—can heighten the audiologist’s appreciation of the familial, social, vocational, and educational impacts of a given hearing loss and more closely adheres to the principles of clinical best practice.14

We see only a small slice of our patients’ lives with hearing loss. We are not privy to the many struggles that may lead someone to call for an appointment. Nor can we appreciate the ongoing hearing challenges that patients may face after we have fit them with hearing instrumentation and put their charts into the system for periodic follow-up visits. While we are aware that hearing aids do not restore hearing to normal, we often proceed with the dispensation of our responsibilities as if our role in hearing remediation is complete following the hearing instrument fitting. For most patients who wish to regain their previously active lifestyle in spite of worsening hearing, we can do more. Yet, without further assessment on the front end, we are often unaware that additional services would be advantageous.

The use of pre- and post-treatment self-assessment measures is recognized as part of best practice services.14 Despite their value in assessing the personal impact of hearing loss,15,16 determining specific communication needs,17 and increasing patient motivation to follow treatment recommendations,1-3 most of us do not use self-assessment questionnaires in the evaluation process.9,18

In tandem with self-assessments in the hearing evaluation, speech-in-noise testing can be useful in determining the degree of difficulty the patient experiences when listening in noise in order to guide instrumentation selection and to assess remaining difficulties following fittings. As Taylor19 points out, a rapid determination of an aided signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) loss greater than 10 dB on the QuickSIN20 provides objective data that additional rehabilitative measures or technologies are warranted beyond amplification alone.

Speech-in-noise tests also lend a high degree of face validity to hearing testing given that the primary hearing complaint of most patients is hearing in background noise. In addition to the value of these tests from a management perspective, one must wonder what patients think if we fail to assess their primary complaint. In spite of the growing ease of administration of speech-in-noise testing, surveys show such tests are not routinely done.9,21

The addition of these self-assessment measures and speech-in-noise testing takes little clinical time and quickly helps differentiate our services from the competition. These measures also provide heightened insight into the needs of patients, and bring the clinician more closely in line with best-practice guidelines.

#3) Augmentative Technologies

Certainly, there are many persons with moderate or even moderately severe hearing loss who function to their own perceived level of satisfaction with no more than properly fit hearing aids. But even these individuals frequently find benefit from supplemental rehabilitation and are pleased to discover that ongoing communication frustrations can indeed be lessened. Depending on the patient’s lifestyle, communication needs, and degree of hearing loss, the extent of treatment beyond hearing aids may vary.

One easy addition to the services provided is to give an introduction to augmentative technologies. About 18 years ago, a survey found that patients were informed of hearing assistance technologies (HAT) 34% of the time.18 More recently, Clark et al9 reported that only 13% of surveyed audiologists routinely discussed HATs with their patients. It is difficult to explain this decrease, but it may be related to audiologists’ perception that the advances in hearing aids are better meeting listener needs. While advances are remarkable in many ways, we do need to keep in mind the residual hearing deficits present with even the best technologies (see Table 1).

An assistive technologies exploration questionnaire is a time-efficient means to increase clinical discussions of HATs.22 Such a questionnaire can be completed in the waiting room for patients returning for hearing aid or cochlear implant follow-up services. The audiologist’s review of this form can quickly identify specific areas that may benefit from further assistance and can facilitate and streamline discussions and hearing assistance technologies selection.

Consumers with hearing loss have lamented the lack of information given about assistive technologies and have repeatedly spoken of their desire for their HCPs to be more forthright in their discussions on this topic.23 Indeed, in many states the profession is seeing consumer-driven legislation enacted to ensure hearing professionals inform their patients of the value and uses of a telecoil, a primary assistive technology.24,25 Similarly, many people with hearing impairment can benefit from a captioned telephone, usually provided free once the hearing loss is certified by the HCP.

#4) Communication Management

Twenty years ago, Kochkin and Rogin26 reported that while the use of hearing aids was highly beneficial, many of the negative impacts of hearing loss—including family discord, frustration, and social isolation—persist to a lesser degree with hearing aid use largely due to the residual hearing deficit. The Clark, Huff and Earl9 survey found that only 19% of audiologists regularly provide communication management handouts to patients, with another 23% noting they often do so. It would appear that nearly 50% of audiologists provide such handouts infrequently or not at all despite best-practice recommendations.

However, we should recognize that the provision of a list of communication strategies (tell others you have a hearing loss, ask your communication partner to move away from a noise source, etc) may be of limited value in and of itself. In fact, the provision of such lists void of discussions to promote their use may be little more than a “feel good” nod toward hearing rehabilitation on the part of the audiologist.

Adults with hearing loss continue to be impacted by the stigma, both perceived and real, associated with hearing aid use.27,28 A primary mechanism for coping with disability is to avoid drawing attention to one’s difference.29 Yet, the very use of the communication suggestions that audiologists frequently recommend draws attention to exactly what the patient is not wanting to draw attention to. As such, we might question the effective provision of communication management strategies without exploration of self-efficacy and comfort of use.

Motivational engagement tools of importance/comfort rankings, perceived self-efficacy for use, and when needed, cons vs pros decisional balances1-3 are often recommended to increase hearing aid uptake among those who may be reluctant to follow recommendations. These same tools can be pivotal to adaptation of communication strategies. Professional reluctance toward the use of motivational engagement tools should be introspectively explored by every HCP.30

Low numbers have also been reported for the provision of clear speech instruction to patients and their primary communication partner, for group hearing therapy, or even recommendations for at-home augmentative computer-based aural rehabilitation (eg, neurotone.com; www.sensesynergy.com/readmyquips; lipreading.org; www.clearworks4ears.com; http://angelsound.emilyfufoundation.org).9,18 Providing some means of communication management assistance to offset residual communication difficulties is something we can all do and brings us all more in line with best-practice recommendations.

#5)

Providing Information on Patient Rights

The residual hearing deficits our patients live with day to day create challenges when accessing public services that are a right to all. The Americans with Disabilities Act of 199031 and the Americans with Disabilities Act Amendments Act of 200832 address discrimination prohibitions and speak to the rights of those with hearing loss and other disabilities—rights of which audiology patients are frequently not fully aware. When residual hearing deficits remain with hearing aids or cochlear implantation, employment settings, public venues and attractions, medical practices, courts of law, etc, are required to provide reasonable accommodations to ensure understanding, participation, and safety.

The consumer association, Hearing Loss Association of America (hearingloss.org) provides accessible information on patient rights and other topics, as well as online and group support that all patients should be aware of. Audiologists and other HCPs are creative and innovative people and can find meaningful ways to better disseminate information on patient rights. In keeping with the goal we all share to help those with hearing loss as fully as possible to participate in what life has to offer, we might want, at a minimum, to offer a brochure that outlines patient rights so that all patients can better participate in society.

How Do We Make Changes When Needed?

As noted earlier, change is difficult. We ask our patients to make significant changes in their lives when we recommend hearing aids. We also are capable of making significant changes on behalf of our patients. Toward this end, we may want to look to see where change is needed.

Are we meeting all areas of best practice to ensure the most efficacious treatment for our patients? Many of us are. Of the five areas discussed in this article, some of us may be failing to address one or more. Change can indeed be daunting when confronting multiple changes all at once. It is frequently easier to select a single area, work on that, and once successful move to another.

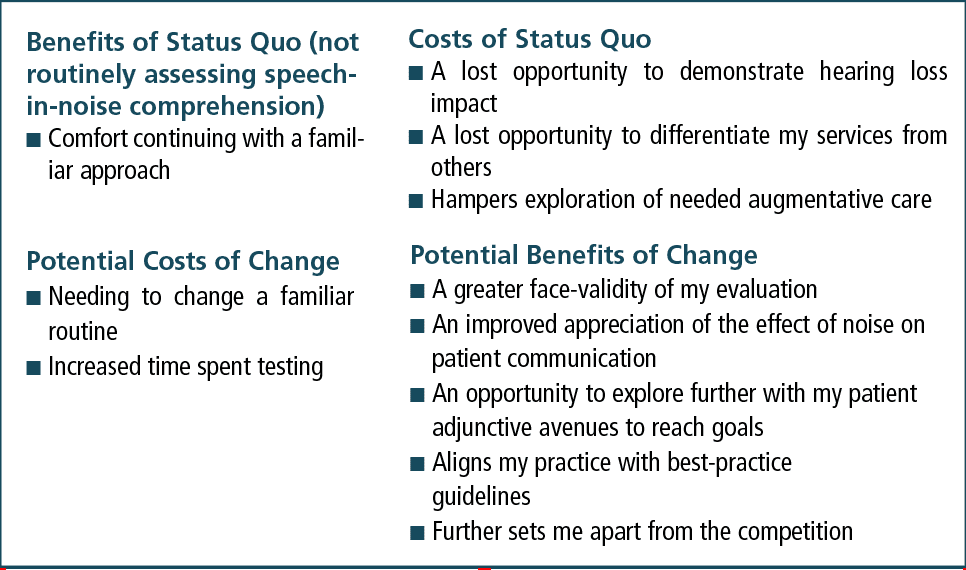

When contemplating changes to the way we practice, we may want to make use of the same motivational techniques that are useful when working with our patients. For example, let’s say I do not complete speech-in-noise testing with patients to help ascertain how much difficulty their remaining hearing loss is affecting their lives after the hearing aid fitting. I might do an importance ranking and ask myself, on a scale of 0 to 10, how important is this to do? If my goal is truly to help those with hearing loss to the greatest extent possible, I would likely rate this very high.

If, on the other hand, I did not see this testing as that important to my practice, I could do a decisional scaling. As seen in Table 2, this introspective exercise shows more advantages to adding speech-in-noise testing to my evaluation protocol than continuing without these measures.

Next, if this exercise convinced me that I should begin using speech competition tests, it would be helpful to question how comfortable I am doing this and what I might need. At this stage, and going forward, I might contact a colleague and enlist him or her as a buddy in this change process, comparing notes and experiences as we make changes together to reach goals of staying professionally current, surpassing our competition, and increasing professional satisfaction. And once we have made the change we started with, we can look to see if there are other changes that might benefit our practices and our patients.

Will OTCs Change Professional Practice?

The recent move toward over-the-counter hearing aids may prove to be the very impetus that audiology needs to more fully embrace its rehabilitative roots. Nearly 50 years ago, when arguing against the ASHA ban on hearing aid dispensing, audiology proponents of dispensing vociferously maintained that audiologists, by virtue of their training, were best prepared to manage the ramifications of hearing loss. Unfortunately, when the dispensing ban was lifted in the 1970s, audiologists largely embraced the same dispensing protocols used by hearing instrument specialists. Audiology’s roots are in hearing rehabilitation, yet the opportunity to bring a greater rehabilitative focus to the dispensing process failed to materialize.

Audiologists have a renewed opportunity to embrace more fully the important task of providing a greater array of hearing loss management services to the growing population living with diminishing hearing. Treatment should not end with the fitting of amplification. If we all move toward Sweetow’s Functional Communication Assessment11 and use assessment findings to provide services, such as augmentative technologies exploration, communication management discussions, and wider patient education, then our patients and our practices will be the better for it.

I remember a patient lament, “I’m hearing much better with my new hearing aids. But I still need a lot of repetitions, and there are still a lot of frustrations. I wish there were more that I could do.” Fortunately, there is! Perhaps OTCs will provide the impetus for the change that we need to broaden our focus so that patient’s residual difficulties are more meaningfully lessened.

Remembering our motivation to enter this profession, and upholding our shared goal to assist those with hearing loss as fully as we can, this change is possible.

Correspondence to Dr Clark at: clarkj6@ucmail.uc.edu.

Citation for this article: Clark JG. How to differentiate your patient care with 5 best practices. Hearing Review. 2020;27(9):12-16.

References

1. Clark JG. The geometry of patient motivation: Circles, lines, and boxes. Audiology Today. 2010;22(4):32-40.

2. Clark JG, English KM, eds. Counseling-infused Audiologic Care. 3rd ed. Inkus Press;2019.

3. Fergusen M, Maidment D, Russell N, Gregory M, Nicholson R. Motivational engagement in first-time hearing aid users: A feasibility study.Int J Audiol. 2016;55(S3):S23-S33.

4. Mendel LL, Owen SR. A study of recorded versus live voice word recognition. Int J Audiol. 2011;50(10):688-693.

5. Roeser RJ, ed. Roeser’s Audiology Desk Reference. 2nd ed. Thieme Medical Publishers; 2013.

6. Dillon H, ed. Hearing Aids. 2nd ed. Thieme Medical Publishers; 2012.

7. Clark JG. Uses and abuses of hearing loss classification. ASHA: A Journal of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. 1981;23(7):493-500.

8. Goodman A. Reference zero levels for pure-tone audiometer. ASHA: A Journal of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. 1965;7:262-263.

9. Clark JG, Huff C, Earl B. Clinical practice report card: Are we meeting best-practice standards for adult hearing rehabilitation. Audiology Today. 2017; 29(6):15-25.

10. Hawkins DB, Cook JA. Hearing aid software predictive gain values: How accurate are they? Hear Jour. 2003;56(7):26-34.

11. Mueller HG. 20Q: Real-ear probe-microphone measures–30 years of progress? AudiologyOnline. www.audiologyonline.com/articles/20q-probe-mic-measures-12410. Published January 13, 2014..

12. Mueller HG, Picou EM. Survey examines popularity of real-ear probe-microphone measures. Hear Jour. 2010;63(5):27-32.

13. Sweetow RW. Instead of a hearing aid evaluation, let’s assess functional communication ability. Hear Jour. 2007;60(9):26-31.

14. American Academy of Audiology. Audiologic management of adult hearing impairment: Summary guidelines. Audiology Today. 2006;18:32-36.

15. Newman CW, Weinstein BE, Jacobson GP, Hug GA. The Hearing Handicap Inventory for adults: Psychometric adequacy and audiometric correlates. Ear Hear. 1990;11(6):430-433.

16. Schow RL, Nerbonne MA. Communication screening profile: Use with elderly clients. Ear Hear.1982;3(3):135-147.

17. Dillon H, James A, Ginis J. Client-Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) and its relationship to several measures of benefit and satisfaction provided by hearing aids. J Am Acad Audiol. 1997;8(1):27-43.

18. Stika CJ, Ross M, Cuevas C. Hearing aid services and satisfaction: The consumer viewpoint. Hearing Loss. 2002;May/June): 25-31.

19. Taylor B. Using scientifically validated tests in the timeless art of relationship building. Audiology Today. 2012;24:30-39.

20. Etymōtic Research. Quick SIN Speech-in-noise test, Version 1.3. https://www.etymotic.com/auditory-research/speech-in-noise-tests/quicksin.html.

21. Cavitt K, Tress S. Survey of Clinical Practice. Capstone project, Northwestern University;2019.

22. Clark J, Gilb B. HAT awareness and efficiency may be the key to increased use. Audiology Today. 2019;31(2):72-78.

23. Cohen H, Ellertsen P. Building self-efficacy: Four foundational best practices. Paper presented at: Tenth International Adult Aural Rehabilitation Conference; November 4, 2019; Woburn, MA.

24. Hearing Loss Association of America (HLAA). Consumer protection bill for people with hearing loss signed by New Mexico Governor. https://www.hearingloss.org/consumer-protection-bill-for-people-with-hearing-loss-signed-by-new-mexico-governor. Published April 4, 2019.

25. Frazier S. Hearing loops get the vote. Sound & Communications. https://www.soundandcommunications.com/hearing-loops-get-vote/. Published November 2, 2016.

26. Kochkin S, Rogin C. Quantifying the obvious: The impact of hearing instruments on quality of life. Hearing Review. 2000;7(1):6-34.

27. David D, Zoizner G, Werner P. Self-stigma and age-related hearing loss: A qualitative study of stigma formation and dimensions. Am J Audiol. 2018; 27(1):126-136.

28. Southall K, Gagné JP, Jennings MB. The sociological effects of stigma: Applications to people with an acquired hearing loss. In: Montano JJ, Spitzer JB, eds. Adult Audiologic Rehabilitation. 3rd ed. Plural Publishing;2021:59-76.

29. Hetu R. The stigma attached to hearing impairment. Scand Audiol. 1996;43:12-24.

30. Harvey MA, Citron D. The Tevye phenomenon: Why one may be ambivalent about using motivational engagement tools. Hearing Review. 2020;27(1):14-19.

31. Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Accessibility Guidelines for Buildings and Facilities; Architectural Barriers Act (ABA) Accessibility Guidelines. Federal Register (2004).

32. Americans with Disabilities Act Amendments Act 2008. Public Law 110-325 (2008). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-110publ325/pdf/PLAW-110publ325.pdf.