Patient Care | February 2023 Hearing Review

”Human beings, who are almost unique in having the ability to learn from the experience of others, are also remarkable for their apparent disinclination to do so.” – Douglas Adams

By Michael A. Harvey, PhD

During my over 40-year tenure as a psychologist, I have worked with many families with aged parents dealing with hearing loss. But this time, the parent is my mother.

One day, after we exchanged our greetings in the nursing home, my mother went blank, looked away, and uttered:

“I don’t know who I am anymore. I’m not a wife like I was, I’m not a secretary like I was, and I have no purpose. Who am I? What am I supposed to do? How did I even get here?”

Now 93 years old, she gave up on her life when she lost her vision ten years ago. Previously, she had been an avid reader. Every Sunday morning, she would call family and friends to discuss the latest book reviews and plan what they would read next. But no more. Then came losing her husband, difficulty breathing due to COPD, dementia, and diminished hearing (a moderately-severe bilateral sensorineural hearing loss). Whereas she can understand conversation on a 1:1 basis in a quiet room, she cannot understand others if they are more than 10 feet away.

In a fledgling attempt to continue the conversation, I said she must be bored during the day, having nothing to do. “You can’t read, watch TV, and you don’t visit anyone!” Her response: “I enjoy sleeping.” Then I brought up an irritating subject to her; audiobooks. She could no longer read, but she could hear if she would only agree to use amplification (a familiar refrain). As predicted, she countered, with irritation, that “I don’t like people reading to me.” A minute later (not realizing the irony of her next statement), she said, “Thankfully, someone comes every week to read me my mail.”

“I’m sorry, mom, I’m confused. You said you don’t like audiobooks. I thought you said you’ve never tried them?”

“I haven’t!” (Mild impatience)

“Now I’m really confused! I could have sworn you said you don’t like them!”

“I don’t.” (Marked impatience)

There is a quotation by cartoonist Jhonen Vásquez, “Nothing quite brings out the zest for life in a person like the thought of their impending death.” Obviously, he has never met my mother. She has been depressed but continues to ignore good advice to get therapy or take medication. My wife once offered to take her to a beach to enjoy the feel of the sand and the ocean air. My mother almost bit off her face for such a preposterous idea! Per the quotation by Douglas Adams at the beginning of this article, my mother was disinclined to learn from the experience of others who have successfully received treatment for their depression and hearing loss.

Alongside my heartbreak to see my mom this way, I have to admit that I felt mild irritation, even anger. Although I cannot know what it’s like to lose my hearing or vision, I know many people who have been both blind and deaf since birth, dual disorders that I cannot begin to imagine, yet they, too, somehow retain their zest for life. Why can’t my mother? Or why won’t she?

Stubbornness comes to mind. Granted, it’s not a professional term. I wouldn’t describe a patient in this manner. Instead, I would practice reflective listening, validation, collaboration, motivational interviewing, etc. But this is my mom, not my patient. As her son, it’s easier for me to feel angry than to bear witness to her despair.

A paradox. She has a right to die. She would welcome euthanasia in a heartbeat. I recall, as an adolescent garnering my accrued wisdom to convince my terminally ill grandfather that his life was worth living. Looking back through an adult lens, I suppose my grandpa’s imminent death may have been a good idea for him, but not for me. Perhaps the same is true for my mom waiting to die. An essential question: What do you want? There is a Dennis the Menace cartoon in which Dennis was trying to be helpful to an elderly lady by leading her across the street. She was yelling, “I don’t wanna cross!” He should have asked her first.

But what if mom is not competent to answer the “What do you want?” question? As an analogy, I recall reading Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave.” The allegory begins with prisoners who have lived their entire lives chained inside a cave. Behind the prisoners is a fire that casts shadows on the wall. The prisoners watch these shadows, believing this to be their reality as they’ve known nothing else. Plato posits that one prisoner becomes free and finally sees the fire, and realizes the shadows are fake. Then they escape from the cave and discover a whole new world that had been outside their awareness.

Perhaps my mother is stuck in that cave, not realizing she could escape and improve her quality of life. The Self cannot exist in isolation. I’m reminded of the movie, “Cast Away,” starring Tom Hanks as a FedEx worker whose plane crashes on a tropical island. He finds himself without much of a future and without hope of ever getting back to civilization. He shouts, “Hello? Anybody?” at the sand and trees. And when he realizes he’s all alone, he paints a face on a volleyball and names it Wilson 一 a device which, not incidentally, gives him an excuse for talking out loud and for imagining Wilson talking back to him. He even risks his life to save his talking volleyball. Astronauts are keenly aware of this concept. In the isolation of space, they must depend on routines, tasks, and orders from earthbound command centers to keep their psychological orientation.

This principle is quite relevant for persons with hearing loss who succumb to isolation. There is mounting evidence that better hearing allows one to engage in mentally stimulating and challenging activities, which will have a positive impact on our brain, cognitive reserve, quality of life, and overall health.1 Stated differently, without adequate hearing and other stimulation, our brain atrophies. We no longer know who we are. We become trapped in Plato’s cave. In psychological vernacular, our cohesive sense of Self the “totality of our being” becomes fragmented.2 Imagine a shattered mirror.

My initial formulation: Spending endless hours with minimal visual, auditory, and interpersonal stimulation has caused my mother to lose her cohesive Self. In her words, “I don’t know who I am anymore.” I must convince her to reverse this downward spiral.

My plea: “Mom, reading books was your lifeline. Audiobooks are better than nothing! You can’t improve your vision, COPD, or dementia and bring your husband back. But an audiologist showed me many amplification devices that she said will help you hear better both with books and people around you! Why won’t you take her advice?” Round two.

“Stop lecturing me, young man!” she scowled.

“Mom, I’m not a young man; I’m 70 years old!”

“You’re a young man to me. I remember how long it took me to toilet-train you. You would poop when and where you wanted to and – “

“Mom, I appreciate you toilet training me; I really do. So does my wife. But -“

“Gawd, how you would carry on. You were so stubborn!”

What? Now she’s calling me stubborn! Here we were, engulfed in a power struggle over who’s more stubborn, this time not about my pooping but hearing aids and audiobooks!

It’s tempting to attribute mom’s refusal to use amplification and audiobooks to her difficulties with technology. She hasn’t used a computer for a decade and cannot reliably operate a landline telephone despite repeated trials. However, she never once said she doesn’t want to use the phone. She desperately wants to be able to call her children. She can’t operate a phone but won’t attempt to use any simple amplification device or audiobooks.

What to do? Clearly, our power struggle would get both of us nowhere. On reflection, I came to realize that it was an oversimplification to label mom as stubborn.

It was easier to get angry at her when she wasn’t helping herself in the way I think she should and to assign myself the role of eradicating her stubbornness than to acknowledge my helplessness when watching her wither away. This is termed ambiguous loss.3 We are “stubborn” aka cognitively rigid when we’re terrified of change, including loss. Reading books had served as her psychological anchor, but she was robbed of that anchor.

“How is reading books different from hearing books?” I asked her.

As if she was waiting for me to ask that question finally, she quickly and lucidly responded: “When I read books, I imagine how the characters sound: their tone of voice, vocal inflections, their whispers. Listening to an audiobook robs me of all that.” At that moment, mom came back to life. We were silent for a bit as I took in what she was saying. I learned that besieged by seemingly endless losses, she held on for dear life to her right to imagine how characters in a book sounded. She was determined not to be robbed of that pleasure as well.

My revised formulation: Although long-term stimulus deprivation caused my mother, in her words, to no longer know who she was 一 fragmentation of Self refusing audiobooks and amplification may be her way of holding on to a tenuous “branch”; an act of autonomy which validates her sense of Self.

In this writing, all I have is that “revised formulation.” That and a nickel won’t buy you a cup of coffee. I would love to end this article with “My mother is now hearing better, using audiobooks, and enjoying her remaining time,” but mom told me not to lie (particularly in publications). The truth is nothing has changed. Instead of painting a false rosy picture, let me offer what I have learned from this “journey” and offer suggestions.

Psychotherapy would help mom tremendously, but she wants no part of it, saying she is too busy! Here is my fantasy of how therapy with a fictitious “Dr. Smith” would proceed.

Dr. Smith would begin by validating the emotional enormity of her profound losses, her depression, and her wish to die. He would also affirm her right to choose how she spends her remaining time, even contrary to the onslaught of well-meaning advice from her adult children. Of course, he would acknowledge that using simple hearing aids and audiobooks are not the end-all-be-all, that they wouldn’t cure her macular degeneration, etc. But it would be one thing she could control.

When asking her how she felt about audiobooks, Dr. Smith would use a psychological protocol called Motivational Interviewing.4 Motivational Interviewing (MI) is a protocol to assist people who are resistant to change, including persons with hearing loss who resist amplification.5-7 MI confirms what Sigmund Freud posited: that even when one is resistant to change “I don’t wanna,” there is always some level of ambivalence: “I wanna, but I don’t wanna.”8

In this manner, Dr. Smith would collaborate with her, constantly asking about her thoughts and feelings, but with the warmth and objectivity of a professional. He would not have the baggage that adult children have: to feel not only profound despair and helplessness but, at the same time, to feel angry, even betrayed, by our parents as they lose their faculties and stop acting like parents. Love is complicated.

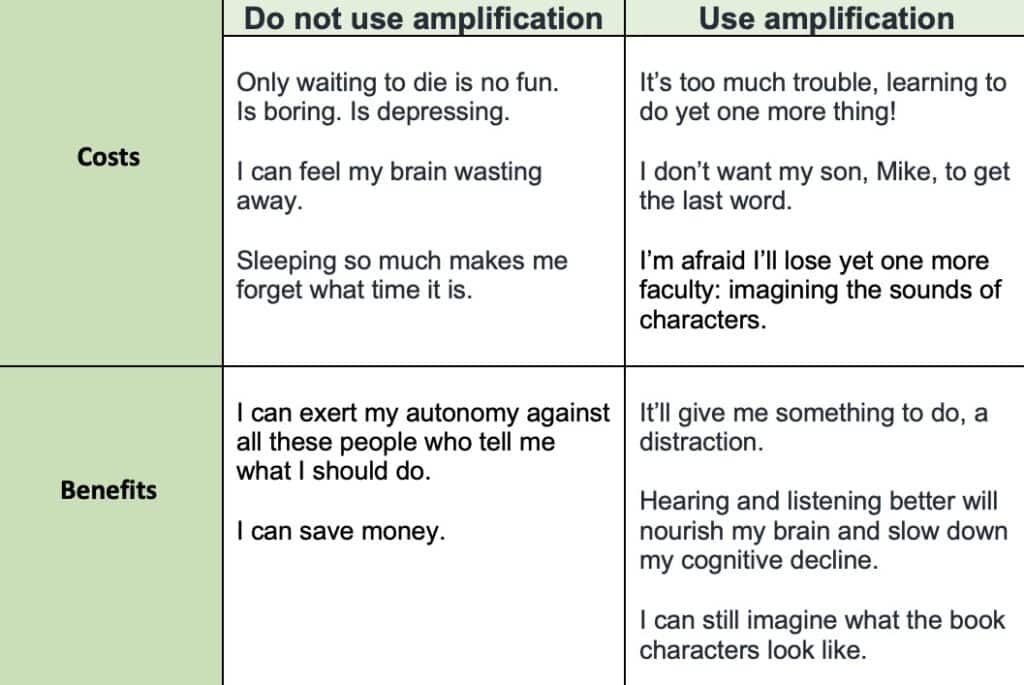

Mom and Dr. Smith would construct the following “Decision Balance Sheet,” a MI tool that would summarize mom’s perception of the costs and benefits of amplification and audiobooks: her ambivalence (Figure 1). Validating one’s ambivalence about change – as opposed to disagreeing or arguing about it (invalidating it) 一 is an effective way of “detoxifying” it, taking away some of its power. The act of really listening and understanding another’s resistance often ushers in deeper therapeutic discussions and sets the stage for positive change.

I imagine that their conversation may go something like this:

Mom: “Mike will not stop badgering me about audiobooks.”

Dr. Smith: “You said you are afraid you’ll incur another loss of yet one more faculty: your ability to imagine the sounds of characters.”

Mom: “Yeh, I do not wanna be robbed of that, too!”

Dr. Smith: “You cherish the ability to use your imagination and are afraid it will be taken away; you will be robbed of that pleasure.”

Mom: [Nods her head.] “I told that to Mike a while ago.”

Dr. Smith: “Isn’t he the one who was so hard to toilet train?”

Mom: “You got that right, Doc. [long description while Dr. Smith repeatedly nods his head]

Dr. Smith’s reference to my childhood pooping struggles would not have come out of thin air. Instead, it is straight out of psychologist Erik Erikson’s description of childhood psychosocial development (Erikson, 1982).9 As infants become toddlers, they learn to walk, crawl, eat, and toilet train on their own. With these new abilities become new choices and struggles for power and control. Do they walk away from their mother to explore the house? Do they refuse food if they are not hungry? Although this stage occurs around age two, variations of these power struggles occur throughout adulthood. Mom exemplified this dynamic with “I can refuse hearing aids and audiobooks.” Her non-adherence to good audiological advice is one of a plethora of documented examples in the audiology literature (Harvey, 2020).10

Dr. Smith: “What do you think his resistance to being toilet trained was telling you?

Mom: “I will do it my way, when and if I want to!” You have no idea how … [long description about how difficult I was]

Dr. Smith: “It sounds like he insisted on the right to poop in whatever manner he imagined. He did not want you to rob him of that right and pleasure.”

Mom: “It was for his own good!” [long description of why]

Dr. Smith: “When we consider doing something, even for our own good, that others are badgering us to do, it is difficult to figure out if we’re doing it for others or ourselves. It’s difficult to preserve our autonomy, isn’t it?

Mom: [Slowly nods her head] “I see what you are getting at. Like me with audiobooks.”

Dr. Smith: “Yeh, you said it on your Decisional Balance Sheet: ‘Mike would get the last word.’ How would you feel if Mike chooses a bunch of audiobooks and then you make sure you listen to anything else except those books?”

Mom: [Big smile] “Good idea! I’ll do that!”

Dr. Smith: “And as you also said on your Decisional Balance Sheet, you can retain the control to imagine what the book characters look like.”

Mom: “That is right. Wow, you’re real smart, Doc.”

I can fantasize, can’t I? Undoubtedly, it would not be this easy. However, the outcome is realistic. Psychotherapy is the art and science of helping persons accept the things they cannot change, garner the courage to change the things they can, and exercise the wisdom to know the difference. The serenity prayer.

In contrast to what my mom cannot change, she can change her level of hearing and listening abilities. Accordingly, Dr. Smith would then discuss various audiological assistive devices, again using the MI protocol. A consulting audiologist would explain that often an elderly person with fine-motor difficulties, poor vision, and dementia would not be able to operate a typical hearing aid. A viable option would be a “Pocket Talker.” It looks like a Walkman, but it’s a basic amplifier with earphones. Another option the audiologist would offer is to have her fit with programmable economy prescription aids, which could be set to lock the volume and other controls in a “set it and forget it” mode. Much simpler than a landline telephone.

Impending death is one thing we cannot control. Therefore, as a compensatory strategy, we may steadfastly 一 aka stubbornly 一 protect what autonomy we have left. I must do what I want, not what others want for me. We can feel assured that our actions are, in fact, autonomous when they are counter to others’ advice, particularly if it is advice with which we secretly agree. In reaction to our acts of autonomy, our loved ones become more concerned, angry, and judgmental, prompting them to increase the frequency and intensity of their advice, prompting us to protect ourselves even more. And round and round we go.

I can imagine a final exchange between Dr. Smith and mom:

Mom: “I know Mike is worried about me, that he loves me, and it is hard for him to see me ending my life this way. He often tells me that when he is not busy seeing patients or writing!”

Dr. Smith: “Do you think he will write an article about you?”

Mom: “Ha. Maybe he will!”

Citation for this article: Harvey MA. Preserving Your Autonomy in the Face of Good Audiological Advice: A Tribute To My Aged Mother. Hearing Review. 2023;30(2):28-31

References

- Beck DL, Harvey M. Issues in cognition, audiology, and amplification. Hearing Review. 2021;28(1):28-33.

- Jung C. Memories, dreams, reflections. Fontana Press. 1995.

- Ross P. Ambiguous loss. Harvard University Press. 2010.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: third edition. New York: The Guilford Press. 2013.

- Beck DL, Harvey MA, Schum DJ. Motivational interviewing and amplification. Hearing Review. 2007;14(11):14-20.

- Beck DL, Harvey, MA. Motivational interviewing. Hearing Professional. 2018;58-65.

- Harvey MA. What your patients may not tell you. Hearing Review. 2010;17(3):12-19.

- Freud S. New introductory lectures on psycho-analysis. New York: W.W. Norton and Company. 1933.

- Erikson EH. The life cycle completed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 1982.

- Harvey MA. The hearing health care journey: putting beans in your cups. Seminars in Hearing. 2020;41(01):68-78.