Staff Standpoint | March 2021 Hearing Review

By Karl Strom, editor

Few expected the ascent of hearables to be a smooth ride. Anyone in the hearing industry can vouch for how difficult it is to engineer, manufacture, market, and distribute a quality hearing aid that turns into a major home-run product, so it wasn’t shocking that two of the forerunners of today’s “hearables market”—the Bragi Dash and Doppler Labs DUBS Acoustic Filters—were discontinued after only a few years of availability. As I noted in a November 2017 editorial about the demise of Doppler, the classic Silicon Valley gripe that “Hardware is hard” can easily be modified to “Hearing is hard.” Companies as large and diverse as Bausch & Lomb and RCA Labs (Songbird Medical) can sadly attest to this fact.

Although Bragi and Dopper products may have failed commercially, they probably paved the way for some other very exciting possibilities in what will someday be the “OTC hearing aid” category, once the FDA establishes regulations for this yet-to-be-defined product class. In my opinion, among the most exciting of these companies include NuHeara, Eargo, Lucid Audio, Lexie Hearing, Alango, iHEAR, SoundWorld Solutions, Olive Union—and the list keeps growing (eg, see Mead Killion and MCK Audio’s latest PSAP). Then there are the heavyweights of Bose, Apple, and Google Alphabet which are all developing products/features that should play at least some role in future amplification options for people with milder hearing losses or even what we currently define as “normal hearing“—and what should serve as gateway products that lead consumers to professionally fit hearing aids. It would also be unwise to count out current hearing aid manufacturers as eventual participants in this market.

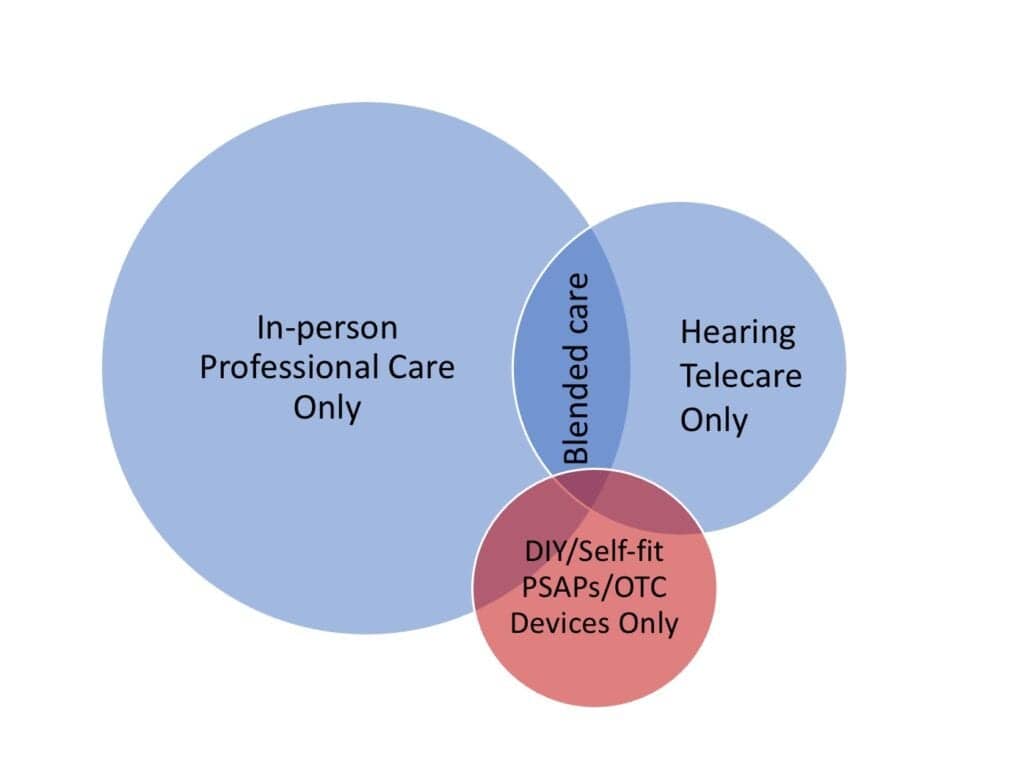

The “blended care model” of hearing healthcare is also producing a diversity of companies, success stories, and disruptive elements. The grandfather of these companies may be Australia’s BlameySaunders Hears (B&S) which combines online marketing, telecare administered by hearing care professionals, and brick-and-mortar hearing care clinics to meet patients “on your terms,” providing consumers with on-the-go adjustments and convenient follow-up options (including in-person care). Similar approaches are used by the VA and UnitedHealthcare, and to some extent by dispensing networks and private practices, particularly during the pandemic. Audicus, Lively, Lexie, Eargo, and iHear are examples of companies using a telecare-only dispensing model, with varied degrees of emphasis in their marketing and positioning about the value of customized fittings and professionally administered hearing care.

These companies, and doubtlessly more to come, operate using procedures that challenge some professionals’ fundamental precepts about professional hearing care, ethics, and responsibilities to the patient. Should a hearing care professional always insist on at least one in-person hearing evaluation for all patients? If not, which patients might be seen via a telecare-only model and which should not? What kinds of procedures and testing typical of current licensing laws, if any, might be waved for certain patient groups in an effort to provide them with better access, convenience, and more affordable professional care (eg, otoscopy, bone-conduction audiometry, etc)? How will the FDA’s OTC hearing device regulations influence or preempt any of this? These are just a few of the tricky questions organizational leaders, licensing boards, company executives, and private practice owners alike are now grappling with.

In February, as this issue of Hearing Review was going to press, a controversial proposed change to Florida’s hearing aid dispensing law caught everyone off guard and immediately jolted us into a reckoning with some telecare-related issues (obviously, these issues have existed for much longer!). Unfortunately, the manner in which this particular legislation was introduced probably evoked a much stronger reaction than what might have resulted from a more inclusive and reasoned vetting of the amendments (see our February 24 news article). HIA and AAA both opposed the legislation on similar grounds: that removal of a professional evaluation is contrary to the best interest of patients with hearing loss, particularly those who may require medical or surgical treatment beyond hearing aids. However, in some ways, the proposed legislation can be seen as a wake-up call—a kind of Fort Sumter moment—that jolts us all into seeking more concrete and evidence-based answers about both the opportunities and challenges that telecare and the “blended care models” pose for the future of hearing healthcare.

About the author: Karl Strom is editor in chief of The Hearing Review and has been reporting on hearing healthcare issues for over 25 years.

Citation for this article: Strom KE. The rise of the disrupters in hearing healthcare. Hearing Review. 2021;28(3):6.