Researchers have developed a behavior change intervention program to help HCPs address patients’ social-emotional well-being in audiological consultations.

By Bec Bennett, PhD

Having strong social connections is essential for good health and well-being throughout life. People who have meaningful social relationships tend to live longer and enjoy better health than those with fewer meaningful connections.1 However, adults with hearing loss face challenges in communication and often develop unhelpful coping strategies over time, which can lead to social isolation and poor mental health. In fact, loneliness and depression are more common among adults with hearing loss compared to those with normal hearing.2,3

Unfortunately, routine audiological care doesn’t always address the social-emotional well-being aspects of hearing loss.4 The good news is that audiologists have the opportunity to play a crucial role in providing support for the mental well-being of their patients.

It has been shown that adults with hearing loss feel better supported and are more likely to engage with their hearing rehabilitation when their audiologist acknowledges their state of social-emotional well-being.5,6 However, audiologists often don’t ask their patients about this,4,7,8 or provide the necessary support when concerns are raised.5 This is due to various barriers, such as a lack of skills, knowledge, time, organizational support, and resources.4,9 Many people, including both consumers and professionals, are now advocating for targeted interventions to address the mental health effects of hearing loss.7,8,10,11

My research team, which included 10 other researchers from across Australia, set out to develop and evaluate a behavior change intervention to increase the frequency of social-emotional well-being support provided within routine audiology consultations.

Figure 1. The AIMER program aims to enhance audiologists Asking, Informing, Managing, Encouraging, and Referring clients for social-emotional well-being support.

Behavior Change Intervention

In our research, intervention development was guided by the Behavior Change Wheel (BCW),12 an eight-step, systematic process for developing multifaceted behavior change interventions.

Steps 1-3: Understanding the Problem

This phase involved (1) Defining the problem in behavioral terms; (2) Selecting the target behavior(s); and (3) Specifying the target behavior(s). To achieve this, we conducted a series of stakeholder workshops involving adults with hearing loss and their significant others, as well as hearing healthcare professionals (audiologists, reception staff, and managers).10

During these workshops, participants discussed and defined the problem behavior, defined as “Providing psychosocial and social-emotional well-being support for adults with hearing loss.” The top behaviors voted by participants to be the most promising for a behavioral intervention were further specified to form the three behaviors targeted by our intervention:

(1) asking clients about their social-emotional well-being;

(2) providing general information on the social-emotional well-being impacts of hearing loss; and

(3) providing personalized information on managing the social-emotional well-being impacts of hearing loss.

Step 4: Mapping the Behavioral Landscape

This phase involved identifying what in the person(s) and/or environment(s) needed to change for the target behaviors to occur. This was achieved through a series of focus groups and semi-structured interviews with audiologists exploring the barriers and facilitators influencing the three target behaviors using a framework called the COM-B model of behavior change.8,13 The COM-B model recognizes that barriers and facilitators of behavior change may relate to capability (e.g., skills, knowledge), opportunity (e.g., social influences, physical environment), or motivation (e.g., beliefs, intentions, emotional responses, habitual responses). The model proposes that if a behavior is not taking place, barriers in one or more of these areas need to be addressed.

The following barriers were identified in relation to the three target behaviors of the intervention.

1. Asking about social-emotional well-being.8 All participating audiologists described firsthand experiences of discussing social-emotional well-being within clinical encounters; however, they tended to wait for the client to raise the topic of mental health impacts of hearing loss and rarely asked about clients’ well-being directly.

The main barriers preventing audiologists from asking about social-emotional well-being related to lack of knowledge and skills to ask about social-emotional well-being (capability); lack of time and resources (opportunity); limiting beliefs about how clients might respond to being asked about well-being (motivation); limiting beliefs about the benefits of asking about emotions (motivation); and uncertainty about audiologists’ scope of practice (motivation).

2. Providing general information on the social-emotional well-being impacts of hearing loss.13 Participating audiologists demonstrated a high level of understanding regarding the range of social-emotional well-being impacts of hearing loss and appeared motivated to provide general information to clients regarding mental health; however, most described not performing this behavior routinely.

Barriers to information sharing included lack of time and resources (opportunity); low confidence in their ability to accurately relay the information (motivation); concern that not all clients would be open to receiving this sort of information (motivation); and feeling unsupported by managers and colleagues (opportunity).

3. Providing personalized information on managing social-emotional well-being.13 Participating audiologists were cognizant of the need to provide information on well-being management strategies and help-seeking options and demonstrated a general desire to do so. However, barriers preventing audiologists from routinely providing information on managing social-emotional well-being related to limited knowledge regarding which clients require this information (capability); what sort of information to provide (capability); how to present and discuss the information (capability); and time pressures and lack of resources for providing this information (opportunity).

Participants also described being inhibited by a lack of knowledge regarding who, when, and how to refer for psychological services (capability), as well as perceiving a lack of psychology services and practitioners skilled to meet the unique needs of adults with hearing loss (motivation).

Steps 5-8: Identifying Intervention Functions and Content

In this phase, the research team made structured decisions regarding prioritization of the behavioral diagnosis (selecting the top barriers to focus the intervention on) and identified intervention functions (e.g. education and training), policy categories (e.g. guidelines), and behavior change techniques (e.g., adding objects as prompts and reminders to the environment) from the literature to address these core barriers. The research team and representatives from our clinical partner (clinicians and managers) brainstormed possible translation pathways for intervention content, gathering evidence through reviewing the literature regarding the impact of intervention functions on the target behavior from other contexts.

The output of this process was a codeveloped, multi-faceted behavior change intervention aiming to improve how audiologists provide social-emotional well-being support to clients experiencing social challenges or emotional distress on account of their hearing loss.

The resultant intervention, the Ask, Inform, Manage, Encourage, Refer (AIMER) intervention,14 incorporated a variety of intervention functions and behavior change techniques. These include training (e.g. training workshops to improve knowledge of psychosocial symptoms, management option and help-seeking pathways, and self-led training resources to help with language development for asking about and discussing emotional well-being), clinical resources (e.g., clinical discussion tools, shared decision-making tools, and client take-home information sheets), workflow changes (such as client survey and case note prompts), and endorsement from credible sources (Figure 1).14

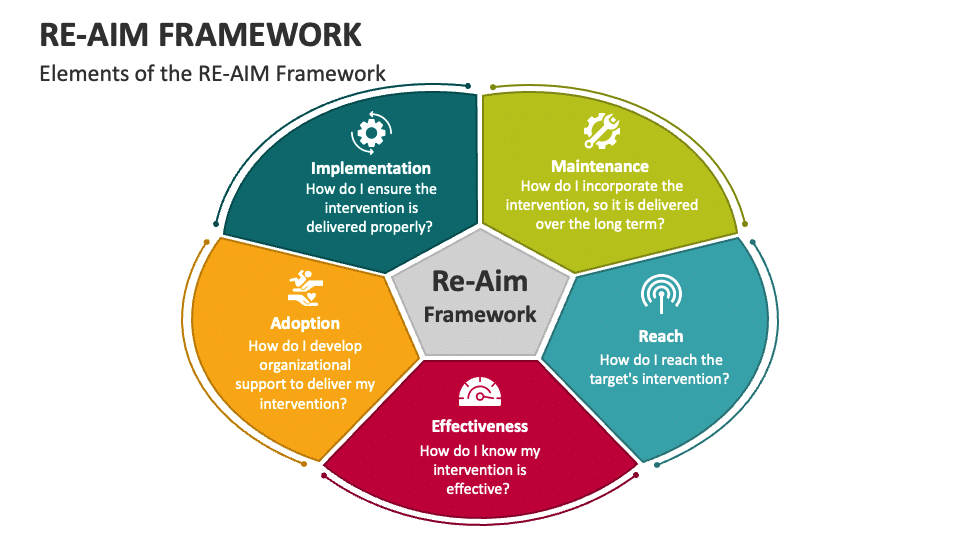

Figure 2. The Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework.16

Application of the RE-AIM Implementation Framework

We systematically evaluated the first iteration of the AIMER program to determine whether the intervention achieved the changes in audiologist behaviors anticipated and to evaluate feasibility of implementing the AIMER program based on the implementation protocol.15 The AIMER program was implemented within a large hearing services organization between October 2020 and February 2022.

The Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework,16 a theoretical model providing a structure for assessment of implementation pathways, was used to guide this evaluation (Figure 2). RE-AIM comprises five dimensions:

- Reach – Did I reach the targeted population with the intervention?

- Effectiveness – Was the intervention effective?

- Adoption – Did I develop organizational support to deliver my intervention?

- Implementation – Was the intervention delivered properly?

- Maintenance – Was the intervention embedded in a way that it becomes a part of routine organizational practice and ensures long-term delivery?

Quantitative and qualitative methods were used to collect and analyze information about the AIMER program’s activities, characteristics, and outcomes across the five domains of the RE-AIM framework. Data collection methods included: (i) self-report survey; (ii) self-reported clinical diaries; (iii) clinical file audit; and (iv) semi-structured interview.

Comparison between pre- and post-implementation data showed that the AIMER intervention successfully increased:15

- Audiologists’ skills and confidence for discussing social-emotional well-being;

- how often audiologists ask about social-emotional well-being within audiology consultations;

- how often audiologists provide personalized information and support regarding social-emotional well-being within audiology consultations; and

- how often audiologists use social-emotional well-being terms within clinical case notes and GP reports.

In conclusion, the AIMER program was shown to be effective at increasing the frequency with which audiologists ask about and provide information regarding social-emotional well-being within routine audiological service delivery. The findings of this study will be used to further adapt and improve the AIMER program and to enhance program implementation strategies prior to its further dissemination.

Accessing the AIMER Program

You can freely download the paper describing the development of the AIMER,14 which includes a link to access and download the resources we have developed.

We encourage clinicians to adapt these resources to suit their clinical practice and work environment. Feel free to customize them according to your needs and integrate them into your clinical practice. It would be wonderful to see these resources being used worldwide.

If you have any questions about how to use the resources or any feedback on how we can improve them, or even stories of how you have used them in your clinic, please don’t hesitate to reach out to me at [email protected]. I would love to hear from you.

Resources produced as part of this program included two videos wherein adults with hearing loss share their personal stories of how hearing loss can affect social and emotional well-being. We encourage you to view these videos and share them with your clients as a means of offering validation and support for their experiences:

Where to Next?

AIMER-online is on the way. We are currently working on designing a research program to digitize the entire AIMER intervention program. This would allow organizations from around the world to access all the training materials, train themselves and their colleagues, and provide holistic social-emotional well-being support to their clients.

Acknowledgments

We couldn’t have completed this work without the help of HCPs and people with real-life experience of hearing loss, guiding our work and participating in our studies – thank you.

This work was funded by the Raine Medical Research Foundation; thank you.

About the Author: Bec Bennett, BSc (Hons), MAud, MBus, Grad Dip Couns, PhD, is a clinical audiologist and senior research audiologist at National Acoustic Laboratories in Sydney, Australia, and an adjunct senior research fellow at Ear Science Institute Australia and the University of Western Australia. Her research focuses on adult audiological rehabilitation, teleaudiology service delivery, and the social and emotional impacts of hearing loss. She is a NHMRC Investigator Fellow and a director of the board, Audiology Australia.

References:

- Lim M, Holt-Lunstad J, Badcock J. Loneliness: contemporary insights into causes, correlates, and consequences. Springer; 2020.

- Shukla A, Harper M, Pedersen E, et al. Hearing Loss, Loneliness, and Social Isolation: A Systematic Review. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 2020;162(5):622-633.

- Lawrence BJ, Jayakody DM, Bennett RJ, Eikelboom RH, Gasson N, Friedland PL. Hearing loss and depression in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Gerontologist. 2020;60(3):e137-154.

- Bennett RJ, Meyer CJ, Ryan B, Eikelboom RH. How do audiologists respond to symptoms of mental illness in the audiological setting? Three case vignettes. Ear and Hearing. 2020;41(6):1675-1683.

- Ekberg K, Grenness C, Hickson L. Addressing patients’ psychosocial concerns regarding hearing aids within audiology appointments for older adults. American Journal of Audiology. 2014;23(3):337-350.

- Laird EC, Bennett RJ, Barr CM, Bryant CA. Experiences of Hearing Loss and Audiological Rehabilitation for Older Adults With Comorbid Psychological Symptoms: A Qualitative Study. American Journal of Audiology. 2020 29(4):809-824.

- Bennett RJ, Donaldson S, Mansourian Y, et al. Perspectives on Mental Health Screening in the Audiology Setting: A Focus Group Study Involving Clinical and Nonclinical Staff. American Journal of Audiology. 2021;30(4):980-993.

- Nickbakht M, Meyer CJ, Saulsman L, et al. Barriers and facilitators to asking adults with hearing loss about their emotional and psychological well-being: a COM-B analysis. International Journal of Audiology. 2022:1-9.

- Bennett RJ, Meyer CJ, Ryan B, Barr C, Laird E, Eikelboom RH. Knowledge, beliefs, and practices of Australian audiologists in addressing the mental health needs of adults with hearing loss. American journal of audiology. 2020;29(2):129-142.

- Bennett RJ, Donaldson S, Kelsall-Foreman I, et al. Addressing emotional and psychological problems associated with hearing loss: Perspective of consumer and community representatives. American Journal of Audiology. 2021;30(4):1130-1138.

- Australian Government Department of Health. Report of the Independent review of the hearing services program. https://www.health.gov.au/news/report-of-the-independent-review-of-the-hearing-services-program

- Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The behaviour change wheel: A guide to designing interventions. Silverback; 2014.

- Bennett RJ, Nickbakht M, Saulsman L, et al. Providing information on mental well-being during audiological consultations: exploring barriers and facilitators using the COM-B model. International Journal of Audiology. 2022:1-9.

- Bennett RJ, Bucks RS, Saulsman L, Pachana NA, Eikelboom RH, Meyer CJ. Use of the Behaviour Change Wheel to design an intervention to improve the provision of mental wellbeing support within the audiology setting. Implementation science communications. 2023;4(1):1-22.

- Bennett R, Bucks R, Saulsman L, Pachana N, Eikelboom R, Meyer C. Evaluation of the AIMER intervention and its implementation targeting the provision of mental wellbeing support within the audiology setting: a RE-AIM analysis. Ear and Hearing 2023;Under review – Submitted March 2023

- Glasgow RE, Harden SM, Gaglio B, et al. RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Frontiers in public health. 2019;7:64.

Original citation for this article: Bennett B, A Framework to Provide Mental Health Support for Hearing Loss. Hearing Review. 2024;31(6):24-27.

Lead Photo: Dreamstime