A systematic review of the literature on diabetes, its potential impacts on hearing loss, and a discussion of the clinical implications.

By Emily Urry, PhD and Elizabeth Stewart, AuD, PhD

Across a lifespan, an individual’s hearing capacity is influenced by genetic, biological, psychosocial, and environmental factors. These factors can either lead to hearing loss or protect against it.1 The link between diabetes and hearing capacity hit the headlines in recent years due to the American Diabetes Association (ADA)2 and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recognizing diabetes as a risk factor for hearing loss. Indeed, as per ADA’s website: “…if you live with diabetes, you are twice as likely to experience hearing loss.” However, in academia, the association between diabetes and hearing loss remains somewhat controversial. Study findings are often weakened by the use of self-reported outcome measures or an incomplete collection of medical history (e.g., noise exposure, medication with ototoxic properties) and confounding factors such as age, sex, duration of diabetes, and smoking.3

Diabetes mellitus occurs when raised blood glucose levels persist because the body cannot produce or use insulin effectively. Diabetes can damage many of the body’s organs, leading to serious complications such as cardiovascular diseases and nerve, kidney, and eye damage.4 Both diabetes and hearing loss are age-related and highly prevalent conditions. Specifically, 537 million people live with diabetes worldwide (about one in 10)4 while disabling hearing loss affects 430 million people.5 Clarifying their association is essential for enabling evidence-based narratives in clinics and providing holistic and person-centered care—an emerging goal in hearing healthcare.6 Thus, a literature search was executed to ensure a systematic identification, assessment, and analysis of high-quality data on the association between hearing loss and diabetes, with the goal of providing an overview of the association.

Methods

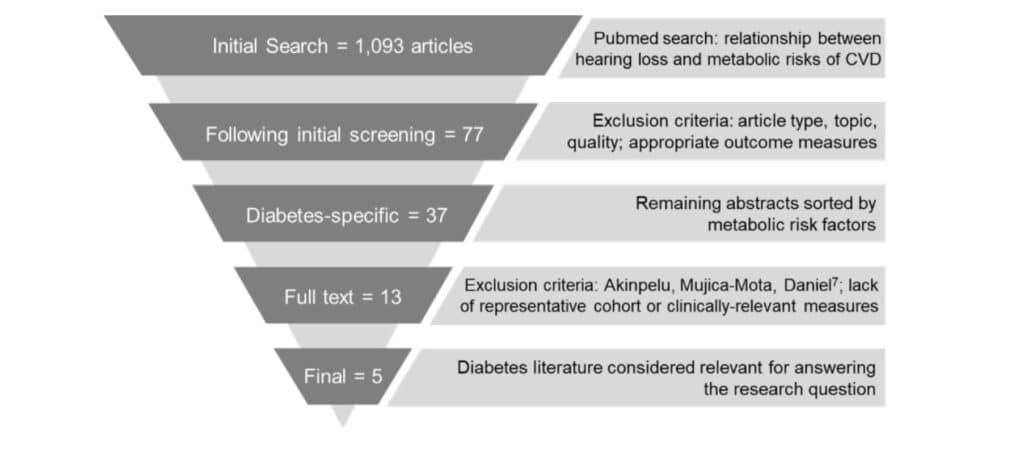

Relevant evidence was identified as part of a broader literature search investigating the relationship between hearing loss and metabolic risks of cardiovascular disease (CVD)—including diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia (e.g., high cholesterol). The initial search yielded 1,093 abstracts, which were screened for relevance to the research question and quality of evidence (Figure 1).

Examples of exclusion criteria used during abstract screening included:

- Papers other than peer-reviewed journal articles (e.g., editorials, opinion papers, technical papers, conference posters, etc.)

- Studies in which hearing status and metabolic risk factors for CVD were not the primary focus of the study

- Studies in which hearing and/or metabolic risk factors for CVD were measured subjectively (e.g., self-report)

- Studies related to treatment of CVD metabolic risk factors

- Studies in children and teenagers

- Studies focused on gestational diabetes

The 77 articles that met the screening criteria were then classified according to the metabolic risk captured by study outcome measures. The relationship between hearing loss and diabetes was the most frequently investigated, with 37 potentially relevant articles.

Due to the high number of diabetes papers, only those examining type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) were included—this type typically developed in older age and is thus the most representative of the target population. Further, the most recent meta-analysis regarding the association between hearing loss and T2DM7 was used as a cornerstone in that the exclusion criteria used by the authors were applied to the present analysis; in addition, all papers covered by the time range of their search (all available papers up to April 2013) were removed.

This resulted in 11 remaining papers regarding the diabetes risk factor and hearing loss. An additional two studies identified during the full-text review were considered relevant, for a total of 13 full-text articles assessed for relevance to the research question. Of these, one article was excluded due to use of self-report for the diabetes measure (not identified during abstract screening), and an additional seven were omitted due to the inclusion of a participant cohort not representative of the population of interest or outcome measures not reflective of hearing status, as measured clinically. Thus, five articles were used to summarize the evidence regarding the association between hearing loss and T2DM.

Findings

Detailed analysis of the remaining five studies led to the following conclusions:

- T2DM is associated with poorer hearing sensitivity.7-11

- Hearing loss is significantly more prevalent in groups with T2DM, compared to groups without diabetes.7-11 For example, the systematic review and meta-analysis of 18 studies by Akinpelu, Mujica-Mota, and Daniel7 showed that overall, the prevalence of hearing loss was nearly twice as high (1.91x) in the diabetes group. Indeed, the prevalence of hearing loss ranged between 44% and 70% for T2DM groups, significantly higher than in control groups (20% to 49%). Interestingly, the authors also found that auditory brainstem response results showed prolonged wave V latencies in the T2DM groups compared to the control groups, suggesting reduced retrocochlear function in individuals with diabetes, relative to those without.7

- Individuals with T2DM are more likely to suffer from mild hearing loss (hearing thresholds 26-40 dB HL)12 at high conventional audiometric frequencies (4-8 kHz) compared to individuals without T2DM.7,8,10,11 Since this pattern is consistent with the presentation of age-related hearing loss, these results suggest that diabetes may speed up the progression of age-related hearing loss or even induce an earlier-than-usual onset.7

- Preliminary evidence revealed significantly lower distortion product otoacoustic emission (DPOAE) amplitudes in T2DM patients8,9,11 and pre-T2DM,8 relative to non-T2DM controls.

This finding suggests that this quick and easily-administered objective measure of hearing function may be useful in identifying negative effects of T2DM on cochlear and retrocochlear function that are detectable prior to audiometric changes. That is, with further research, OAE testing may be an eligible examination for early identification of hearing impairment in T2DM patients.9

Does diabetes cause hearing loss?

The potential causal mechanisms underlying the association between diabetes and hearing loss are still under debate. It could be argued that the increased prevalence of hearing loss in T2DM is simply a correlation due to shared biological processes. However, research in humans and animals suggests that diabetes, which damages other parts of the body (e.g., eyes, kidneys) via small blood vessels and nerve dysfunction, may similarly impair the functioning of the inner ear.3 For example, evidence from at least one human temporal bone study revealed significant thickening of the walls of cochlear blood vessels, as well as atrophy of the stria vascularis and outer hair cell loss—all of which may result in or contribute to hearing impairment in individuals with T2DM compared to non-diabetic controls.13

Limitations and future research recommendations

The present literature review revealed insufficient evidence to reliably explain and define the effect of both the duration of diabetes and the sex of patients on the association between T2DM and hearing loss. Since about 17.7 million more men than women are living with diabetes,4 it would be important to investigate sex differences in the association between diabetes and auditory function. Further, in order to better understand the link between impaired blood glucose regulation and reduced auditory function more broadly, high-quality longitudinal studies are required. Here, objective hearing and diabetes-related data should be collected over time to elucidate their potential causal relationship, to clarify sub-groups of diabetes patients, particularly at risk of hearing loss, and to identify interventions to reduce said risk.

Clinical implications for audiologists

In adults aged 65 or older, a core patient population in hearing care, an estimated 33% have diabetes.14 Hearing care professionals should be aware that diabetes increases the risk of developing hearing loss and may accelerate its progression. Therefore, when taking a case history at an initial consultation, a question about diabetes status should be included, as well as any family history of the disease (a significant risk factor for diabetes).4 In subsequent sessions, any changes in health status and medication intake should be discussed. More broadly, patients should be encouraged to lead healthy, active lifestyles. Smoking and poor nutrition are risk factors for both T2DM4 and hearing loss and should be avoided, while regular physical activity, which improves health and reduces diabetes risk14, should be promoted. HR

Emily Urry, PhD, is an experienced clinical health scientist whose work focuses on cardio-metabolic health promotion via health behavior change. At Sonova, she runs a program that explores the health challenges of people with hearing loss and ways to address said challenges. Elizabeth Stewart, AuD, PhD, is a senior research audiologist in the Phonak Audiology Research Center (Sonova US). She manages various external study collaborations and supports background research activities relevant to Phonak and other Sonova initiatives.

References

- World report on hearing. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. In: World Health Organization (WHO); 2021: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/world-report-on-hearing.

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice C, American Diabetes Association Professional Practice C, Draznin B, et al. 4. Comprehensive Medical Evaluation and Assessment of Comorbidities: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(Suppl 1):S46-S59.

- Samocha-Bonet D, Wu B, Ryugo DK. Diabetes mellitus and hearing loss: A review. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;71:101423.

- IDF Diabetes Atlas (10th ed.). In: International Diabetes Federation (IDF); 2021: https://diabetesatlas.org/atlas/tenth-edition/.

- Deafness and hearing loss. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/health-topics/hearing-loss#tab=tab_2. Accessed 10 March 2023.

- Maidment DW, Wallhagen MI, Dowd K, et al. New horizons in holistic, person-centred health promotion for hearing healthcare. Age Ageing. 2023;52(2).

- Akinpelu OV, Mujica-Mota M, Daniel SJ. Is type 2 diabetes mellitus associated with alterations in hearing? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(3):767-776.

- Li J, Zhang Y, Fu X, et al. Alteration of auditory function in type 2 diabetic and pre-diabetic patients. Acta Otolaryngol. 2018;138(6):542-547.

- Li Y, Liu B, Li J, Xin L, Zhou Q. Early detection of hearing impairment in type 2 diabetic patients. Acta Otolaryngol. 2020;140(2):133-139.

- Ren H, Wang Z, Mao Z, et al. Hearing Loss in Type 2 Diabetes in Association with Diabetic Neuropathy. Arch Med Res. 2017;48(7):631-637.

- Ren J, Ma F, Zhou Y, et al. Hearing impairment in type 2 diabetics and patients with early diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes Complications. 2018;32(6):575-579.

- Fukushima H, Cureoglu S, Schachern PA, Paparella MM, Harada T, Oktay MF. Effects of type 2 diabetes mellitus on cochlear structure in humans. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132(9):934-938.

- Diabetes and older adults. Endocrine Society. https://www.endocrine.org/patient-engagement/endocrine-library/diabetes-and-older-adults. Published January 2022. Accessed 23 February 2023.

- WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour: at a glance. 2020;Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.