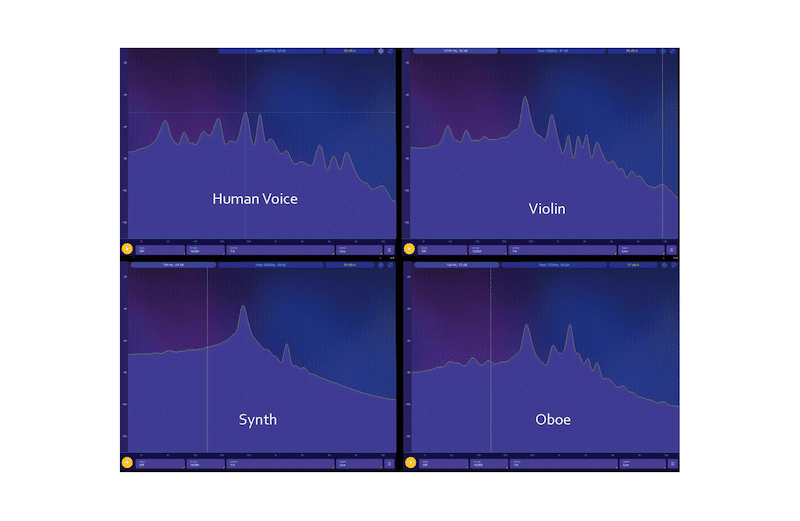

Featured image: Cochlear implants can technically cover the pitch range of a violin and oboe equally well, but the violin requires more accurate pitch perception to hear not only the pitch, but the timbre, which are the harmonic patterns that make instruments playing the same note sound different. Photo: Dreamstime

By Brad Ingrao

As recently as a few years ago, most cochlear implant patients were handed off to a specialty clinic or provider. In the past few years, however, cochlear implant candidacy has changed, allowing more patients with “better” hearing to benefit from cochlear implants. Because of this, it’s more likely than ever that some of your “hearing aid” patients may now have a cochlear implant on one ear. While these two technologies both improve hearing (specifically for speech), they behave differently when music is the input. Let’s take a look at a few of these and see how you can help your patients stay connected to the music they enjoy.

What It Means to be a Cochlear Implant Candidate

“Often, I can scarcely hear anyone speaking to me; the tones yes, but not the actual words; yet as soon as any one shouts, it is unbearable. What will come of all this, heaven only knows!” — Ludwig van Beethoven

This quote really sums it all up. Successful hearing aid users can both hear AND understand. This means that while many of their outer hair cells are shot, they have enough viable inner hair cells to maintain (mostly) accurate pitch perception. Clinically this shows up as aided word recognition better than about 80%. As more inner hair cells die off, word recognition decreases until we get to the current turning point of 60%.

Anyone with aided word recognition below that will be in your office several times a year for an “adjustment” because they hear, but they don’t understand. However, despite your best efforts at programming, they will be back, probably to tell you the recognition has worsened. Cochlear implants are built precisely for this population.

Cochlear Implant 101

Cochlear implants (CIs) are—currently—a two-part hearing system consisting of an internal component (electrode array and receiver/stimulator) and an external component (speech processor).

There are three manufacturers currently approved by the FDA to provide cochlear implants (Advanced Bionics, Cochlear, MedEl). Cochlear implants are usually at least partially covered by Medicare, many private insurance carriers, and the VA and DOD.

Cochlear implant candidacy at the time of this issue grossly follows the “60/60 rule” of 60 dB pure tone average and/or best word recognition (unaided) under 60%. This screening can be done by any hearing care professional. CI candidates should be referred to an audiologist or ENT office trained in cochlear implant evaluation and programming. Each manufacturer has a “find a clinic” link on their website, as does the American Cochlear Implant Alliance, which is a great one-stop shop for information, research, and support for patients considering cochlear implantation.

After “activation” or “initial stimulation” of the device, CI recipients usually have an aided sound field audiogram between 20 and 30 dB from 500Hz to 6000 Hz. Most patients report that speech sounds robotic or like Mickey Mouse. Based on over 20 years of doing this, nearly all of my patients understand speech better (in quiet and moderate noise) than they did at their candidacy evaluation by the end of the second year post-surgery.

All that’s cool, but where does music fit into this? Well, the CI marketing folks also promise a lot there, but as with all things audiology “it depends.” Let’s look at a few things about cochlear implants that may impact hearing music and an approach to bringing music back into our patients’ lives.

Frequency Response of Cochlear Implants

While music perception is clearly on the radar of cochlear implant manufacturers, understanding speech is, and has always been, the primary design deliverable. Marshall Chasin, AuD, an audiologist and director of auditory research at the Musicians’ Clinics of Canada, has shown the differences between speech and music and how that makes hearing aids tough.

Further reading: Hearing Aid Frequency Response Characteristics for Music

With CIs, there are two challenges: a relatively narrow frequency range and a smaller set of channels than the ear. The graph below shows the general frequency ranges for each currently FDA-approved cochlear implant system.

| Manufacturer | Processor | Low Frequency | High Frequency |

| Advanced Bionics | Marvel CIM/Sky CI | 200 Hz | 10000 Hz |

| Cochlear | Nucleus 8/Kanso 2 | 188 Hz | 7938 Hz |

| Med-El | Sonnet 2/Rondo 3 | 70 Hz | 8500 Hz |

If we look at the ranges of some common instruments in the graph below, there doesn’t really seem like much of an issue:

| Instrument | Low Frequency | High Frequency |

| Violin | G3 (196.0 Hz) | E7 (2637.0 Hz) |

| Viola | C3 (130.8 Hz) | C6 (1046.5 Hz) |

| Cello | C2 (65.4 Hz) | E5 (659.3 Hz) |

| Double Bass | E1(41.2 Hz) | B3(246.9 Hz) |

| Flute | C4 (261.6 Hz) | C7 (2093.0 Hz) |

| Oboe | Bb3 (233 Hz) | F6 (1396.9 Hz) |

| Clarinet (Bb) | D3 (146.8 Hz) | Bb6 (1864.7 Hz) |

| Bass Clarinet (Bb) | D2 (73.4 Hz) | F5 (698.5 Hz) |

| Bassoon | Bb1 (58.3 Hz) | Bb5 (932.3Hz) |

| Horn (double, F & Bb) | B1 (61.7 Hz) | F5 (698.5 Hz) |

| Trumpet (Bb) | E3 (164.8 Hz) | Bb5 (932.3Hz) |

| Trombone (tenor) | E2 (82.4 Hz) | Bb4 (466.2 Hz) |

| Timpani | F2 (87.3 Hz) | F4 (349.2 Hz) |

| Harp | B0 (30.9 Hz) | G#7 (3322.4 Hz) |

The problem stems from the difference between the structure of speech sounds and musical notes. Speech sounds (phonemes) are essentially a very simple musical chord consisting of a primary tone (fundamental) and two harmonic resonances. CIs can handle this level of complexity quite well.

However, even though many instruments fit into the frequency range of CIs, that’s only the fundamentals. In Figure 1, we can see frequency responses for four instruments playing the same fundamental note (440 Hz or A4 on a piano).

Figure 1. Frequency responses for four instruments playing the same fundamental note (440 Hz or A4 on a piano). Each of these instruments covers similar overall frequency ranges; we can clearly see that each one has a very different pattern of energy.

Each of these instruments covers similar overall frequency ranges; we can clearly see that each one has a very different pattern of energy above the fundamental.

CIs can technically cover the pitch range of a violin and oboe equally well, but the violin requires more accurate pitch perception to hear not only the pitch, but the timbre, which are the harmonic patterns that make instruments playing the same note sound different. Because of this, many CI recipients find their favorite music sounds odd, out of tune, or just plain unpleasant.

Can we program our way around this? Yes and no. We can apply the same “do no harm” advice we use in hearing aids to reduce compression and disable automatic processing, but for many CI recipients, at least in the first few years of electrical hearing, we serve them better by helping them find instruments and music that fit their new hearing reality rather than trying to adjust settings.

The Current State of Hearing for Music

The rehabilitation plan for music starts by defining the patient’s “current state” of musical hearing ability. I use a Roland Aerophone to create MIDI versions of instruments sampled from real instruments. We pick a few bars of a piece of music the patient knows well, and I play that passage using several “voicings” in the Aerophone.

For each sample I have them rate how true each of the following statements is from 1 (false) to 5 (true), with 3 being neutral:

- “I hear the rhythm.”

- “I hear separate pitches.”

- “I recognize the instrument.”

- “It sounds pleasant.”

- “It sounds like I remember.”

I usually test the following instruments plus any other specific ones they identify as a past favorite:

- Human voice

- Bassoon

- Cello

- Bass Clarinet

- Oboe

- Violin

- Clarinet

- Flute

- Tenor Saxophone

- Trombone

- Trumpet

- Tuba

- Synthesizer with a very simple sine wave generator

A lecture and demo of this process is available online.

Once we find the best instrument or two, I check their pitch perception in terms of how many pitches they can hear, and how close they can be before they smear together.

For musicians, I play octaves, half-octaves, arpeggios, major scales, and chromatic scales. This gives me a sense for how complex the music can be before it sounds muffled or just “bad.”

You can hear samples of this process on SoundCloud.

The final step is for them to list their five most favorite songs or pieces of music from before their hearing began to deteriorate and identify the primary emotions those songs evoked within them.

Further reading: Hearing SoundTracks, Musical Roads, and Pathways

Getting Reacquainted with Music

From here, I teach patients how to search online music streaming platforms like Apple Music, Amazon Music, or Spotify to find music featuring their best two instruments and how to create and tag them into playlists for each emotion previously identified.

The goal is to have them continuously build a library of music they have never heard (so it can’t be negatively compared to how it used to be) and that consistently and successfully connects them to the emotions reminiscent of their favorite, but currently “lost,” music.

After a few months, we reassess and hopefully add another instrument or two to the list. This continues for a year or so until they are able to listen to, and appreciate, songs of similar complexity to their “lost” music, and hopefully some new—to them—music in their old favorite instruments.

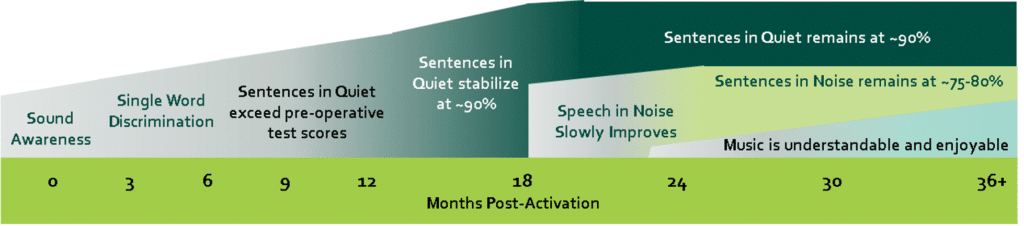

A few years may seem like a long time, but in my more than 20 years working with CIs, that’s just how long it takes. Of course, some will progress faster, but on average, the progression of electrical hearing in the majority of my patients looks like Figure 2.

The old adage “under promise and over deliver” applies here. The problem with being more optimistic in our prognosis is that most of the time, people getting CIs in 2023 should have sought them out years ago. This is not to disrespect their pre-implant provider, but the fact is that referrals are rarely provided until the patient has been failing to thrive with hearing aids (and therefore a likely CI candidate) for many years. The longer that period of effective deafness (candidate, but not yet implanted), the slower the progress will be.

Conclusion (or Coda)

Patients with cochlear implants can have success with music, but it requires a lot of work, and being open to new musical styles and instruments.

For providers, it requires that we be proactive and very data-driven when patients with poor inner hair cell function ask us about a new hearing aid. If we can get them into a CI as soon as they qualify, we can help them do better more quickly for all inputs, including music. Referring these people for CI evaluation is never “losing” a hearing aid customer; it’s more of a graduation to the next things they need in life. Their gratitude and referrals will more than make up for the “lost” hearing aids in the future.

Brad Ingrao, AuD, is known as an early adopter of technologies, a computer geek, and an author and lecturer who makes complex topics understandable. His clinical practice encompasses the entire spectrum of audiology care with particular focus on severe to profound hearing loss, including cochlear implants, hearing assistive technologies, and hearing loss prevention and treatment for musicians. He has worked in private practice, in educational audiology, for the hearing aid industry, at the VA, and has taught at three universities. He has presented at professional and consumer conferences across the U.S., Canada, and Europe.

Original citation for this article: Ingrao B. The Sojourn to Sound: Helping Cochlear Implant Recipients Improve Their Relationship with Music. Hearing Review. 2024;31(1):18-21.

Hi Brad

I enjoyed your article on a CI wearers relationship to music and am going to further investigate the sound testing you offer.

I’m a musician and used to play the piano and sing professionally. A high frequency hearing loss runs through my family.

I’m totally deaf in both ears now. I LOVE my CI and I hear speech quite well and I caught on immediately.

I also started collecting music on Amazon and it has been wonderful. I especially like to listen through Bluetooth with my Kanso 2 from Cochlear.

I always want to help others so I put my 800 songs spanning from 1938 with Benny Goodman to songs to early 1980’s and present it in an internet RADIO form. The songs shuffle through a variety of genres.

It’s a free offering, and perhaps some of your clients might find it fun and helpful to listen .

I still play the piano (I play by ear, but I no longer sing. I’m so off tune. Any ideas would be helpful.

I’ll leave my Radio website for you. Thanks for the work you do.

Love and Light

Nanette